Thailand: Planting seeds of doubt

As sporadic tensions flare over US-China trade, a fierce debate also continues at home, centred on whether Thailand should join a trade pact touted as creating the third-largest free trade area in the world.

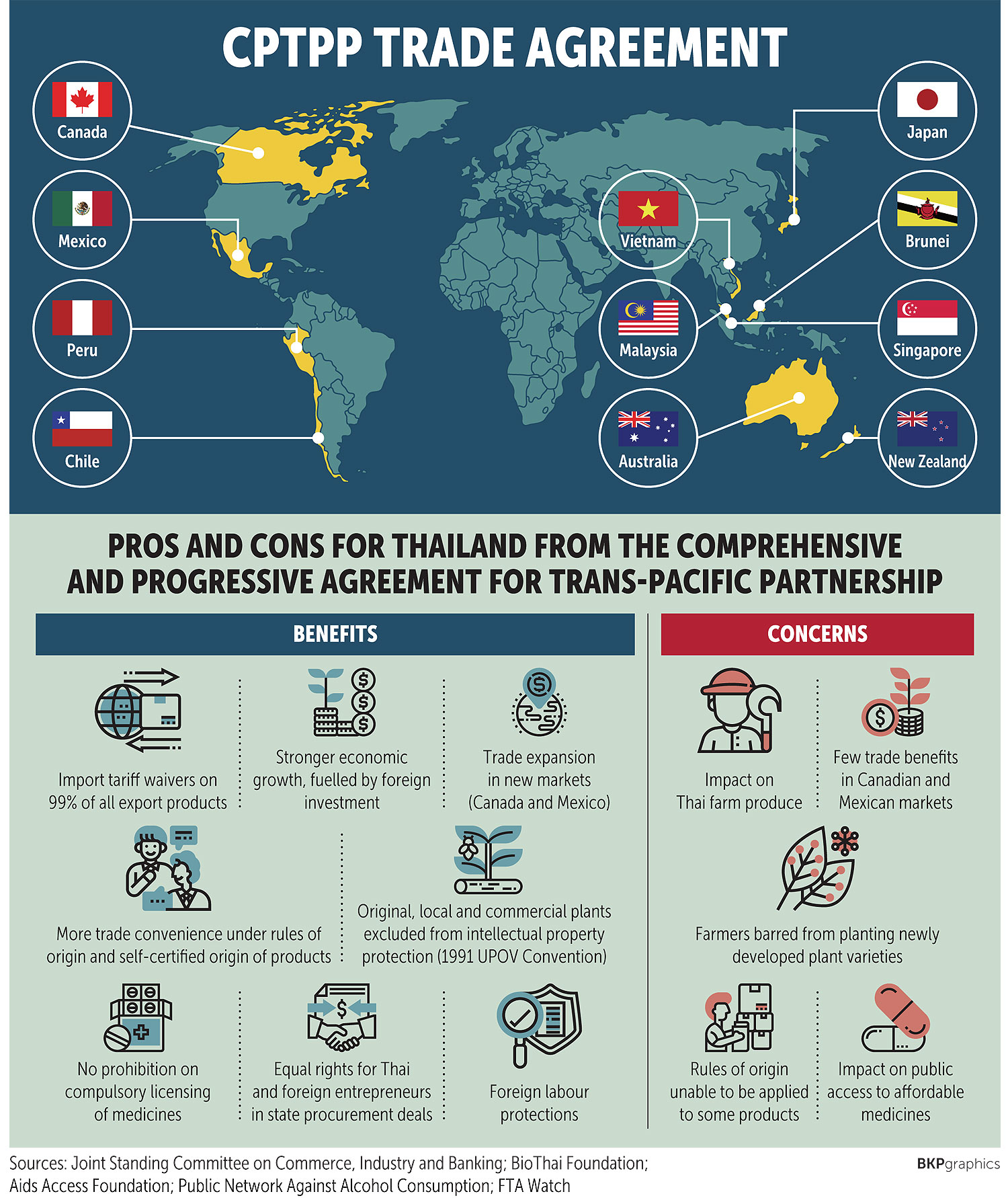

The Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) is a trade agreement involving a newly formed bloc of 11 Pacific Rim nations excluding the US.

The 11 member nations are Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore and Vietnam. The pact came into force in December 2018.

So far Japan, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Mexico, Singapore and Vietnam have ratified the pact.

CPTPP negotiations started after the Trans-Pacific Partnership agreement reached a stalemate following the withdrawal of the US in January 2017.

Thai farmers and civil society organisations expressed concern about the impact of the new pact’s intellectual property provisions, which prevent them from saving and reusing seeds that contain patented plant materials. But officials insist that farmers would still have the right to collect and reuse seeds, but only for non-commercial purposes.

Critics are also concerned about some CPTPP provisions having an impact on access to affordable medicines, as this matter is related to the protection of intellectual property rights and patents.

“We should at least consider joining the negotiation table and not shut the door on this opportunity, as Thai negotiators could negotiate to retain some privileges for Thai products,” said independent academic Somjai Phagaphasvivat.

Thailand stands to lose out on future foreign direct investment coming into the country if it completely refuses to enter the negotiation process, as foreign investors would opt to invest in other regional countries instead, for tax benefits among other reasons, Mr Somjai said.

A farmer harvests rice. Critics of the CPTPP say the trade agreement will destroy small-scale Thai farmers because Thailand is not a signatory of UPOV 1991. Pongpat Wongyala

UPOV 1991 CONVENTION

Wiwat Salyakamthorn, aka Ajarn Yak, a renowned agricultural scholar and former deputy agriculture and cooperatives minister, said he strongly opposes Thailand joining the CPTPP, noting that Thailand would be required to ratify or accede to the UPOV 1991 Convention (the International Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants).

Accordingly, Thailand would have to amend its Plant Varieties Protection Act (1999), a move that would affect profit-sharing mechanisms related to bio resources and protection of local plant varieties in Thailand.

UPOV is a key condition of the CPTPP meant to protect intellectual property. UPOV’s mission is to provide and promote an effective system of plant variety protection that will encourage plant breeders to develop new varieties.

Thailand is not a signatory of UPOV 1991. The country has the Plant Varieties Protection Act, supervised by the Agriculture and Cooperatives Ministry.

“Thailand is rich in plant varieties with as many as 700-800,000 varieties, thanks to its tropical climate, which led Thailand to become a leading exporter of several farm products such as rice,” said Mr Wiwat, also the chairman of the Agri-nature Foundation. “Thai chillis alone have 100,000 varieties, but we have never disclosed this information to the public.”

According to Mr Wiwat, the UPOV 1991 regulations will call for Thailand to let other signatory countries make use of the seeds of native plants from Thailand for research and create new plant species and have them patented as their own and resell them to Thai farmers.

Farmers are not allowed to collect the plant seeds to reproduce them in the next planting season, except for small cereals grown on the farmers’ land just for subsistence.

“As far as we’re concerned, in past negotiations on the CPTPP, we have never had representatives from the farm sector such as BioThai who are experts and know well the impact of the pact to sit as members of the negotiators,” Mr Wiwat said. “Only representatives of supporting farmers and mercenary academics were allowed to attend the negotiations.”

He suggested the government focus the trade partnership talks on the Asean framework rather than the CPTPP.

“In joining the CPTPP, we have to follow their rules that are already set for the best benefits of their own,” he said. “Liberalism or liberalisation is just a fanciful dream. In the reality of this world, there is no true liberalism or liberalisation. What really exists is the fact that only the giant firms dominate and control the market and are getting richer. We then see that joining the CPTPP will destroy Thai small-scale farmers who are not yet strong and smart enough for any free competition.”

Whether Thailand will gain benefits from the CPTPP depends much on Thailand’s capability to raise its own competitiveness, said Somporn Isvilanonda, a researcher at the Knowledge Network Institute of Thailand.

He noted that Thailand’s competitiveness, particularly in farm products such as rice, tapioca and rubber, has weakened over the past few years.

“UPOV regulations aim to protect intellectual property,” he said. “UPOV’s goal is to provide and promote an effective system of plant variety protection that will encourage plant breeders to develop new varieties and own their patents. I see that it would rather benefit Thailand’s agricultural competitiveness, as it will inspire competition in breed research and development. However, we have to be careful about a possible monopoly in the market and ensure that the seeds will not be too expensive.”

According to Mr Somporn, Thailand’s Plant Varieties Protection Act bars the import and export of plant varieties, meaning Thai breeders who want to develop new breeds are unable to import quality varieties from foreign countries to reproduce new varieties.

This arrangement hinders new variety development, and as a result Thailand’s current variety development has fallen far behind countries like Vietnam, which succeeded in developing a soft-textured rice that is in high demand in the global market.

Mr Somporn said Thailand’s agricultural development needs to focus on two directions: unique organic farm products and value addition to existing mass products.

MUCH TO GAIN?

Thailand is likely to see a boost in economic growth, investment and exports if the country participates in the CPTPP, said Auramon Supthaweethum, director-general of the Trade Negotiations Department.

She cited a study by Bolliger & Co, commissioned by the department, finding that Thailand’s participation in the pact would increase GDP by between 0.07% and 0.22% or US$251.49 million and $754.75 million, with investment up between 5.14% and 6.66% or $4.8 billion and $6.2 billion, and exports rising between 3.47% and 4.63% or $8.8 billion and $11.7 billion.

Without CPTPP membership, Thailand is estimated to lose between $859.3 million and $3.5 billion or 0.25% and 1.01% of GDP, with investment down between 0.49% and 2.11% or $460.6 million and $1.97 billion, and exports falling between 0.19% and 0.75% or $469.8 million and $1.9 billion.

According to the Bolliger study, becoming a member of the CPTPP guarantees preferential and improved quality of market access for Thailand’s goods, services and investment in the countries with which Thailand already has an FTA.

Moreover, the CPTPP offers a significantly expanded range of markets, including those with which Thailand has not FTAs before (Canada and Mexico).

But non-governmental organisations spearheaded by FTA Watch and BioThai, another civic group advocating sustainable agriculture, have raised concerns about the overwhelming disadvantages that CPTPP would bring to Thailand.

Essentially, they warn that the CPTPP will require Thailand to comply with international laws such as UPOV 1991, which will affect the rights and accessibility of small farmers to save commercial seeds for replanting for sale or even using commercial seeds to improve plant quality.

In terms of healthcare, the CPTPP, which enshrines patient rights protection, will make it more difficult for the Public Health Ministry to approve generic drugs made by local companies or even impose compulsory licensing to produce cheap drugs for poor patients.

In terms of public policy, the so-called Investor-State Dispute Settlement will open doors for the government to issue policies to protect public benefits leading foreign investors to sue for compensation in international courts of arbitration.

“Information on the impact of the CPTPP provided by the Department of Trade Negotiations reads like propaganda or gives only half-truths to encourage Thailand to join the CPTPP,” said Witoon Lianchamroon, president of BioThai, referring to a six-page letter posted on the department’s website to clarify concerns.

“In joining the CPTPP, the government is betting Thailand’s farm sector and healthcare for the government to get more than 13 billion baht, which represents only 0.12% of GDP,” he said. “Meanwhile, small farmers need to pay 3-5 times more to buy seeds to harvest.”

Kannikar Kijtiwatchakul, vice-president of FTA Watch, said: “The Covid-19 pandemic shows that Thailand has three strong points, which are public healthcare and affordable medicines, food security among small-scale farmers and small retailers that are able to produce cheap foods, and enough space for government to manoeuvre public policy, such as ordering hospitals and the private sector to comply with lockdown measures and support the state. But these three strong pillars will be affected, weakened or even overridden if Thailand ratifies the CPTPP.”

A farmer harvests rice. Critics of the CPTPP say the trade agreement will destroy small-scale Thai farmers because Thailand is not a signatory of UPOV 1991. Pongpat Wongyala

DISAGREEMENT AT LARGE

The Joint Standing Committee on Commerce, Industry and Banking (JSCCIB), which weighed up the gains and losses of the pact in its latest study, has concluded that the government should not miss an opportunity to join the trade talks.

“Thailand should proceed to become a CPTPP member,” said Supant Mongkolsuthree, a JSCCIB member and chairman of the Federation of Thai Industries. “If the agreement does not benefit the country, it can eventually withdraw.”

He said participation will enable the government to see more clearly whether the CPTPP will boost international trade and foreign investment or put the country in trouble.

The JSCCIB earlier tried to clarify the pros and cons of the CPTPP by hiring the University of the Thai Chamber of Commerce to conduct a study in May.

Researchers listed questions, raised by the CPTPP’s opponents, and looked for answers or measures to allay their concerns, ranging from the impact on agricultural goods as a result of import tariff cuts to prohibition on compulsory licencing to better protect patented medicines.

Some issues, like the adverse impact on farmers and new export opportunities, remain debatable and need further examination, according to the findings.

Not everyone in the business camp agrees with the JSCCIB’s stance.

Thongyoo Kongkhan, adviser chairman of the Land Transport Federation of Thailand, said the CPTTP will cause fresh disruptions in the country.

“If Thailand joins the CPTPP, many local businesses will be killed off due to the flow of foreign businesses into the country under free trade agreements,” he said.

Mr Thongyoo suggested the government focus on other unsettled international pacts, like the trade agreement between Thailand and the EU.

“If the CPTPP is full of benefits, why has the US withdrawn?” he said.

Although Thailand could later opt to leave the pact and revoke its membership, that would require the country to go through another lengthy process, Mr Thongyoo said.

Thailand

Thailand