Thailand: Bridging the gaping wealth chasm

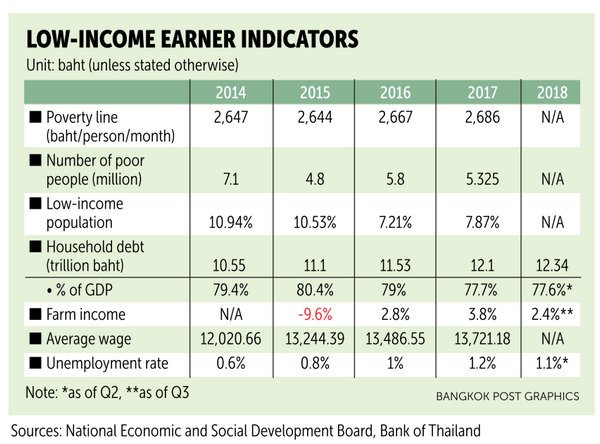

Although the military-led government has rolled out a raft of stimulus and relief measures to shore up the grassroots economy, spending and indebtedness among the underprivileged are still rampant.

Adding to the poor’s predicament is Thailand’s social inequality, which continues to worsen. Credit Suisse’s 2018 Global Wealth Databook reported growing social inequality here, with 1% or about 500,000 of the richest Thais controlling 66.9% of the nation’s wealth.

The country’s GDP growth is on track to rise this year, but the recovery has been uneven as export and service sector tycoons have mostly reaped the benefits, while the agricultural sector, where grassroots workers are employed, has yet to experience robust growth.

“Farm income has actually receded the past several years, while this year’s farm income grew marginally. Crop prices for white rice, rubber and palm oil are still not good,” said Amonthep Chawla, head of research at CIMB Thai Bank.

“A vicious cycle of volatile farm prices will continue to occur if the government does not help in creating value-added farm products to sustain [farmers’] income growth.”

Nominal farm income rose by 3.9% year-on-year in October after a 4% contraction logged the previous month, the Bank of Thailand reported. Agriculture prices declined for three straight quarters this year, falling by 12.2% in the first quarter, 5.9% in the second and 3.3% in the third.

SUPERFICIAL MEASURES

The Prayut Chan-o-cha government has spent 400-500 billion baht for cash handouts and welfare for the poor since taking over in 2014, but state expenditure for national social assistance schemes is too small and not directed to those who are really in need, said Somchai Jitsuchon, research director for inclusive development at the Thailand Development Research Institute.

Social expenditure for OECD countries averages 20% of GDP, but Thailand’s is 7.8%, Mr Somchai said.

The government needs to pump an additional 350 billion baht into its social budget to raise the ratio to 10%, he said.

To fund this amount, the government should slash the country’s defence budget, let the private sector play a leading role in driving the economy to save on economic stimulus spending and raise the value-added tax (VAT) and taxes imposed on assets, Mr Somchai said.

If the poor are affected by a VAT hike, the government can direct incremental tax revenue towards solving the problem, he said.

Although handouts empower the poor to better tailor solutions for their own problems, it does not tackle the root problems of structural inequality and poverty, Mr Somchai said.

Although handouts empower the poor to better tailor solutions for their own problems, it does not tackle the root problems of structural inequality and poverty, Mr Somchai said.

Athiphat Muthitacharoen, an economics lecturer at Chulalongkorn University, said the government’s social measures are superficial and done without systematic analysis, hurting fiscal discipline in the long run.

He criticised the government’s VAT payback scheme for welfare smartcard holders as contradictory, as cardholders’ maximum income is set at 8,000 baht a month, while they need to spend about 10,000 baht a month to get the ceiling 500-baht VAT return.

The government is offering a 86.9-billion-baht splurge to low-income earners and the elderly in the hope that the giveaway will help with living costs and boost the domestic economy.

Social inequality in Thailand has grown during the past three years from large investment projects and concessions given to major businesses, said Anusorn Tamajai, dean and assistant professor at Rangsit University’s faculty of economics.

Although the Eastern Economic Corridor (EEC) projects have benefits, they need to be adjusted to prevent an adverse impact on local communities and the environment, Mr Anusorn said.

One consequence of EEC projects is that villagers have lost their livelihoods and speculation in land in EEC areas is so severe that small and medium-sized businesses cannot afford land resources, he said.

“Land grabs by large foreign capitalists, especially in special economic zones and provinces that are central to the EEC, as well as unclear land information systems will make land reclamation a more serious issue in the future,” Mr Anusorn said.

“Land ownership may affect the use of resources, which the state may have problems controlling. Land reclamation has occurred in many Latin American and African countries and has created imbalances and serious disparities in some.”

ADDRESSING INEQUALITY

Since 2001, successive governments have allocated a combined sum of more than 1 trillion baht to alleviate poverty in Thailand, with half of this amount attributed to the contentious rice-pledging scheme implemented by the Yingluck Shinawatra regime.

The main criteria for identifying low-income earners in Thailand is set at an annual income of below 30,000 baht.

Narumon Pinyosinwat, vice-minister for finance, said Thailand’s poverty problem must be examined from two angles: the number of people living below the poverty line and income inequality.

The government has rolled out measures aimed at addressing poverty, though many perceive them to be populist policies, Ms Narumon said.

For social inequality, the government introduced the inheritance tax and the land and buildings tax, with the latter passed on the National Legislative Assembly’s third hearing, she said.

Thailand’s economic structure is a liberalised capitalist system, and it’s difficult to enlarge state ownership of businesses or raise taxes to generate higher income, then use the revenue for social security, Ms Narumon said.

However, Thailand can help the poor through a social impact fund and social impact bonds, which many countries have begun to adopt.

A social impact fund uses private sector funds for projects aimed at addressing the poor’s plight. Corporations can receive a tax privilege for participating in this programme.

For social impact bonds, the government issues them to raise funds from the private sector to help with social projects. The private sector would be key in overseeing project success.

RECOVERY OUT OF SIGHT

Despite a tranche of relief measures, low-income households remain mired in indebtedness because any money earned is mostly used to service debt, Mr Amonthep said.

Thailand’s household debt rose to 12.3 trillion baht, or 77.6% of GDP, in the year’s second quarter, up from the first quarter’s 12.1 trillion baht, according to Bank of Thailand data.

Enhancing employment opportunities, upgrading skill development and providing digital literacy are Mr Amonthep’s recommendations to develop the grassroots economy and increase income among poor households.

“Education is the [ultimate] long-term solution to solve the grassroots economic problem,” he said. “The government seems to want to address long-term problems, but it also has short-term priorities.”

Adisak Sukumvitaya, board chairman of Singer Thailand, a leading network of direct sales marketers that offers service loans and leasing for consumers, said private consumption in the country has been slowing this year relative to 2017, mainly due to falling crop prices and declining tourism business.

The two sectors account for more than 60% of employment in businesses and services.

“Consumer spending in the overall market has been declining for years, but 2018 has been the hardest,” Mr Adisak said.

He said the decline in consumer spending has created more risk for loan and leasing repayment, meaning loan providers must strictly monitor and manage borrowers.

Failure in proper loan management could cause an increase in non-performing loans in lenders’ portfolios.

Mr Adisak said he has no idea whether the overall economy, especially private consumption, will recover after the scheduled election in February 2019 because consumer spending may take time to bounce back after the formation of a new government.

“It’s too early to believe that private consumption will recover after the election,” he said. “I think businesses may have to be more cautious instead.”

Source: https://www.bangkokpost.com/business/news/1595378/bridging-the-gaping-wealth-chasm

Thailand

Thailand