Thailand: Automation anxiety may be overdone, says ADB

New technologies can both displace and generate jobs. Here in Asia, where demand for goods and services is growing substantially, the number of new jobs being created by new technologies is actually higher than the number they destroy, says the Asian Development Bank (ADB).

Automation anxiety is high among workers and industries that believe they will be affected. Nevertheless, rising demand from a growing middle class and increased productivity from new technologies are offsetting some of the negative impacts of job displacement.

“Asia is still getting richer,” Sameer Khatiwada, an economist with the Economic Research and Regional Cooperation Department of the ADB told Asia Focus at the bank’s annual meeting in Manila early this month.

“Yes, new technologies do displace jobs, they do displace workers, but rising incomes and rising demand lead to the creation of jobs, even in the industries that are being affected by new technology.”

For example, factory automation has long been a fact of life in the automobile and electronics industries. But as incomes rise, more Asians are demanding more cars, more phones and other goods, leading to more jobs across different industries.

The International Labour Organization (ILO) made waves when it forecast recently that at least 25% of jobs in Southeast Asia may be automated in the next two decades. It said 137 million workers or 56% of the salaried workforce from Cambodia, Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam were in the high-risk category.

Mr Khatiwada, a former employment specialist with the ILO in Bangkok, said the UN agency asked employers what kinds of jobs, not tasks, would disappear because of new technology.

“What ADB has done is add more nuance by pointing out that a job is made up of tasks,” he said. “We can’t just ask employers what jobs will disappear, you have to ask them what kinds of tasks will disappear.”

By analysing employment changes in 12 economies in developing Asia from 2005-15, the bank’s Asian Development Outlook 2018 report concludes that technological advances have transformed the 2-billion-worker Asian labour market and created more than 30 million new jobs annually in industry and services.

“The rise of incomes will compensate for job losses due to new technology, and then there will be new occupations in industries that will emerge due to new technology,” Mr Khatiwada argued. “Every single technological breakthrough has led to increases in productivity of workers.”

The report noted that some of the gains reflected shifts in employment from sectors with low productivity and pay, typically subsistence agriculture, to modern industry and services, but a large part of the productivity gains come from technological advances within sectors.

Examples of how workers can be more productive and earn more money include the use of high-yield crop varieties in farming, modern machine tools in manufacturing, along with information and communications technology (ICT) in services.

New technologies automate only “some tasks within job, not all of the job”, stressed Mr Khatiwada.

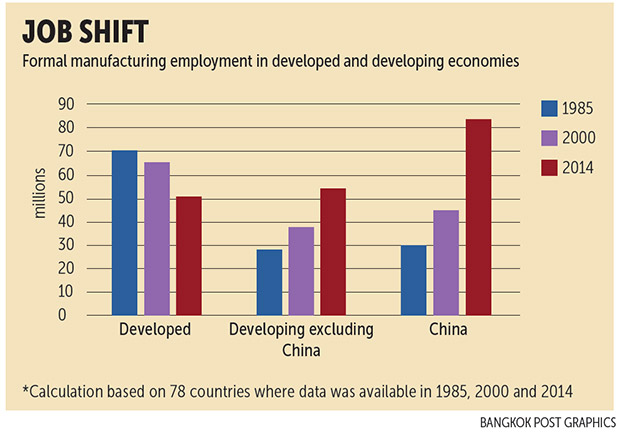

ADB data on industrial robots in Asia showed that the electrical, electronic and automobile industries accounted for 39% of total robot use in 2015 but only 13.4% of total manufacturing employment. By contrast, producers of textiles, apparel and leather goods and food and beverages accounted for only 1.4% of robot usage but 31.4% of manufacturing employment.

“Think of it this way: a task might be feasible to automate but that does not necessarily make it economically feasible. At the end of the day, it has to make business sense to do that,” said Mr Khatiwada.

A job can consist of a “routine task” and a “non-routine task” and these could range from manual to cognitive tasks where “manual and routine” workers such as factory hands will be the most affected by technology.

For example, automation targets mainly routine tasks, such as soldering components onto a circuit board on an assembly line, which is both routine and manual, or counting and dispensing cash in a bank, which is routine and cognitive.

In the 12 economies in developing Asia that account for 90% of employment in the region, 40% of manufacturing and service jobs entail mostly routine tasks, either manual or cognitive. Many of these jobs are unlikely to be lost but some will be restructured as automating others will not be technically or economically feasible.

On the other hand, displacement of “cognitive-routine” workers is becoming a new concern as artificial intelligence advances. For example, it is becoming technically feasible to automate more complex service tasks such as customer support through the use of chatbots.

But “non-routine manual labour” — think of a cook or a hairdresser — appears relatively safe. Basically, it takes a lot more technological sophistication to give a robot the dexterity to stitch cloth, cut hair or make tom yum kung than to handle large metal parts.

Elisabetta Gentile, an ADB economist who co-wrote the report’s chapter on the impact of technology, elaborated on how the increase in demand and adoption of new technology provided a “strong positive employment” effect from 2005-15, in countries from Bangladesh to Taiwan.

“There was an 88% (equal to 134 million jobs per year) increase in employment during this period from increases in external and internal demand and this is a very powerful message, because there is this new Asian middle class that is demanding goods and services and they are driving employment,” she said. “This massive demand is so big that it more than compensates for the loss in employment coming from technology.”

New technologies, she added, allow us to “do more with the limited resources that we have”, and that means producing and selling more goods and services, which feeds right back into the economy and allows people to demand goods and services in the first place.

She also makes the distinction between job and task relocation. For example, an American blue jean manufacturer that does stitching in China might move this task to lower-cost Cambodia because new technology in Chinese factories can perform other tasks.

“There is task relocation going on within the 12 countries observed: for example, manufacturing jobs from Malaysia and the Philippines are being relocated but countries like Thailand, Taiwan and Bangladesh are actually benefiting from task relocation,” she said.

Meanwhile, new technologies have given rise to new occupations and industries such digital artist, web designer and laser sewing machine operator in the textile industry. A detailed analysis of occupation titles in India, Malaysia and the Philippines found that 43% to 57% of new job titles that emerged in the past 10 years are in the ICT field.

“The challenge for workers is to retrain themselves to learn the new skills that they will need to actually take advantage of these new jobs,” said Ms Gentile.

“Education and training is what governments can provide … while favourable labour regulation is needed to find a way to support the transition of these workers from one job to another. The era of one job for one lifetime is pretty much in the past.”

Source: https://www.bangkokpost.com/business/news/1474193/automation-anxiety-may-be-overdone-says-adb

Thailand

Thailand