Insight – RCEP: Breakthrough for Malaysia’s external trade

AT the 4th Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership Summit on Nov 15,2020, the emergence of the world’s largest trade agreement has become the most significant trade policy development.

After almost eight years of negotiation, 15 countries including the 10 Asean members, and five of its dialogue partners (China, Japan, South Korea, New Zealand and Australia), have signed the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) agreement.

Notably, this represents the largest trading bloc to date.

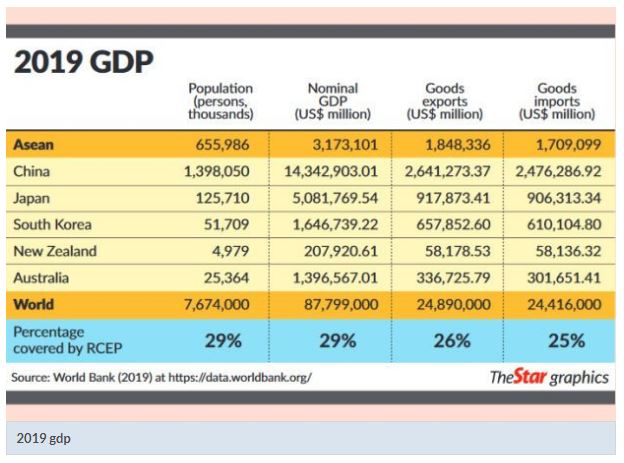

To illustrate, RCEP represents 29% of the global population, 26% of global exports, 25% of global imports and 29% of global gross domestic product (GDP) in 2019 (see table).

Through a streamlined trade agreement, the opportunities from the RCEP deal are moderately immense. In my opinion, this partnership agreement is likely to reduce a range of tariffs on imports within the next 10 to 20 years.

It aims to create an integrated market to ease the provision of goods and services by each member country focusing on trade, investment, intellectual property, e-commerce, small and medium enterprises (SMEs) and economic cooperation.

RCEP is a significant achievement. It involves countries that are from diverse economic stages ranging from those that are least developed, emerging, and advanced economies within the same bloc.

This is likely to reduce the domestic constraints by promoting international trade and comparative advantages to produce goods at a relatively lower production cost among regional markets.

Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership vs. Regional Comprehensive Economic PartnershipCompared with the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), RCEP seems to be less ambitious in scopes covered and depth. There are some significant differentials between these two mega-regional trade deals.

While the CPTPP eliminates tariffs on nearly 96% of products entering the intra-regional trade, RCEP will likely cover 90% of these products.

On the other hand, the provisions of intellectual property (IP) under RCEP will likely add little to those that most members have already accepted in the World Trade Organisation, indicating that RCEP could fall short of the CPTPP in terms of IP.

RCEP also does not cover government subsidy, environmental protection, labour standards and agriculture sector in its agreement compared with the CPTPP that placed a substantial priority in these aspects.

Despite all these, RCEP will remain a substantial agreement with 20 chapters of coverage and effects.

One of the significant advantages is that it offers cumulative and favourable rules of origin for the producers participating in the regional supply network.

RCEP will have immense economic potential through market and job opportunities and provide a transparent, specific, rules-based framework for trade and investment among the participating countries. This safeguards the stability of crucial production networks and value chains.

Asean in the ‘driver’s seat’RCEP signifies the Asean’s central role in the region’s economic landscape because this free trade agreement (FTA) is pre-dominantly Asean-driven. Getting this agreement through, especially when trade protectionism is rising, RCEP is a means to achieve integration among the Asean countries and obtain access to a vast regional market. With these stronger connections, RCEP will encourage further interdependence and help offset distortions created by US-China barriers.

As widely foreseen, RCEP will have more impact on the economy’s supply side or the production chain more than the demand side.

The demand dynamics may not be significant simply because Asia has been benefitting from significant degree of tariff liberalisation through various trade landscapes.

This includes the trade agreements that already exist between Asean countries as well as Asean and China, Asean & Australian and New Zealand.

Although the multilateral trade deal is relatively important, it would not necessarily cast a substantial impact on the demand side. This could be further supported by the fact that external demand persistently overshadows the domestic demand drivers even with various trade deals already in place among the regional markets.

The gains from RCEP agreement are not only limited to the 15 signatories, but the rest of the world are also expected to benefit through the unification of supply chain factors, especially Asean’s regional value chain (RVC) linkages.

According to a report published by Asean Promotion Centre on Trade, Investment and Tourism in 2019, Asean’s participation in global value chains (GVCs) is 61% on average.

This is higher than the worldwide average of 57%. It is also important to note that the importance of RVC has become increasingly significant.

While GVCs have remained almost at the same level since 2015, RVCs have been rising continuously, with Asean alone accounting for 25% of all GVCs.

According to Asean integration report 2019, many supply chains in Asean countries are in industries such as electronics, machineries and automotive.

Since there are tariff liberalisations for these sectors under RCEP, Asean is poised for a sustainable global supply chain in the long run given that there is an increasingly higher demand for these commodities amid the emergence of fourth industrial revolution.

Given that almost 70% to 80% of these industries’ production network are with countries outside Asean, we can expect to see a more diversified supply chain. This would consequently increase the competitiveness among some emerging markets.

Malaysia: Potential gainers and losers Malaysia has the prospects of becoming one of the significant winners of RCEP through broad access to bigger regional market for businesses and foreign direct investment (FDI).

As widely known, this is the first trade agreement to bring China, Japan and South Korea together. The countries are our major trading partners and account for 25% and 18% of Malaysia’s total exports and FDI inflow respectively in 2019.

According to Economist Intelligence Unit’s Business Environment Rankings in 2019, Malaysia tops the Asean countries’ list for competitiveness of emerging market based on few criteria such as FDI policy, foreign trade and exchange policy, labour market standards as well as technological readiness.

Malaysia has already been moving towards positioning itself as a trading and investment hub through various initiatives under the Penjana and Prihatin stimulus packages and Budget 2021 measures. Along with that, RCEP provides even more opportunities for Malaysia to become a growing hub for economic activities in the long term.

In my view, Malaysia’s exports performance is projected to grow substantially with better access to large RCEP markets, given that it is highly integrated into Asean’s RVC and GVCs.

Some industries that may gain from the trade deal include automobile, agribusiness, food and beverages, transport and machineries.

Notably, these sectors accounted for nearly half the percentage of Malaysia’s production network.

In recent months, Electrical and Electronics (E&E) has served as the primary driver of manufacturing sector with significant year-on-year (y-o-y) growth in both the production (average +9.3% y-o-y) and sales (+7.2% y-o-y) since June, quickly rebounding from its severe decline during April (-34.1% y-o-y, -39.6% y-o-y) and May (-11.2% y-o-y, -19.9% y-o-y) 2020.

Since Malaysia’s E&E sector has already been firmly integrated into the global supply chain, little value-added is expected for this sector through the tariff liberalisation. However, the growing demand for semiconductor components such as integrated circuits, memory and microchips necessitates upgrading the value chain.

RCEP can offer a better level playing field for SMEs from both developed and less developed countries.

In this scenario, Malaysia is not an exception in any way given that almost 98% of businesses in Malaysia are comprised of micro, small and medium enterprises.

RCEP has forced China, Japan and South Korea to agree with harmonising tariff concessions compared to the preferential tariffs grants based on business engagement before the RCEP. With that, SMEs can potentially boost their mobility in the regional markets while expanding their market capitalisation, attracting more investments, and diversifying the provision of goods and services.

On the other hand, some industries could lose out to partnering countries mainly due to comparatively higher production costs.

China and Vietnam are widely known for their low production cost in textiles and apparels.

To continue to thrive in the regional markets, these industries must understand where they stand in the entire supply chain and look into strategies to become more competitive in their offerings. Failure to take into account the cost of production would potentially lead to specific sectors to lose out.

Although the RCEP may benefit Malaysia’s economic growth from various perspectives, it would not happen over-night as the positive impacts would take at least a few years to materialise after the ratification of RCEP.

Aside from that, headwinds surrounding the global economic growth and political constraints outside the RCEP countries will still impact the endeavours of this multilateral deal and, consequently, pose uncertainties on Malaysia’s RCEP-induced growth.

Limitations of RCEP

Despite the excellent prospects of RCEP, India’s withdrawal from the world’s largest free trade agreement (FTA) remains a significant disadvantage. However, RCEP members keeps the door open for India to re-join and thus, the probable pact could yet become a game-changer.

With the absence of the United States and withdrawal of India, various stakeholders see that the deal is likely to benefit China, Japan and South Korea more than other member countries.

This is because these countries are large economies, and they accounted for almost 70% of RCEP’s and 25% of global GDP. On top of that, they are not members of any other existing FTAs before signing the RCEP.

Through trade facilitation and trade concessions, the export and imports between these countries can increase compared to within Asean – due to immediate or gradual reduction of applicable tariffs. Potential beneficiary industries include textile, chemical, plastic, E&E products, metal, auto and automobile products.

Second is the non-tariff facilitation. Despite the normal tariff line reduction of 90% over 20 years, what matters the most for manufacturers is the non-tariff barrier liberalisation.

Unlike CPTPP, RCEP agreement focuses on cutting tariffs, which are currently at a low. However, it prohibits the non-tariff barrier on the exports and imports of goods and services.

Facilitation of non-tariff barriers is vital as the tariff reduction primarily to safeguard the infant industries and protect domestic employment. Even though they limit the functioning of a free market, it is equally essential to protect the newcomers from unfair competition by partner countries.

With the trade deal in effect, all the member countries are required to facilitate the non-tariff barrier effectively so that domestic businesses, consumers, social security and environment remain protected.

RCEP is expected to come into effect in early 2022 after at least six Asean and three non-Asean member countries ratified the agreement. In the meantime, businesses are encouraged to consider and analyse opportunities with RCEP from various aspects strategically, including new preferential market, cost saving, optimisation of supply network, and tariff and non-tariff barriers.

As it is usually the case with the other Asean trade agreements, the current provisions under RCEP can be improved and enlarged over time through explicit mechanisms, including the facilitation of non-tariff barrier.

Manokaran Mottain is the Chief Economist at Alliance Bank Malaysia Bhd. The views expressed are the writer’s own.

Source: https://www.thestar.com.my/business/business-news/2021/01/25/insight—rcep-breakthrough-for-malaysias-external-trade

Thailand

Thailand