Exit of Indonesia’s tech whiz kid is a warning to startups

Achmad Zaky spoke with unusual candor after taking the stage in Jakarta that October afternoon. People stopped chattering and lowered their phones when he began recounting the decade he spent building one of Indonesia’s most successful startups. What none of the hundreds in the cavernous hall knew then: it was his last big public act as chief executive of Bukalapak.com.

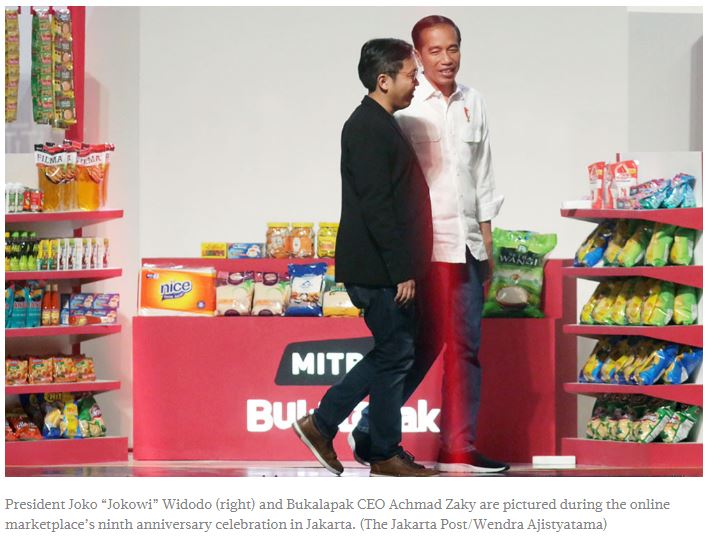

Unbeknownst to the crowd, the 33-year-old self-taught computer whiz was on his way out. After a series of failed experiments and missteps — including an abortive attempt to go toe-to-toe with Alibaba-backed rivals — Zaky had lost his board’s confidence that he could lead a vastly expanded company into its next phase of growth. Just months away from ceding the reins of the $2.5 billion e-commerce outfit he built from the ground up, he spent much of the speech reflecting on his decade-long stewardship.

“I’m not smarter than you. My success rate is maybe 10%,” he told the now-silent audience. “Back then, I was an engineer focusing on the product,” he added. As the company grew, “I was thinking I have to be a leader.”

Yet some of his backers had doubts Zaky was the right person to lead Bukalapak given its current complexity, people familiar with the matter said. That may surprise industry observers for whom Zaky’s name had become synonymous with Indonesian e-commerce. He acquired something akin to folk hero status because, unlike many fellow founders, the self-effacing executive from a Java village made it big without Ivy League degrees or billions from the likes of SoftBank Group Corp.

His departure in January sent a signal to Southeast Asia’s largest startups, which unlike Silicon Valley remains largely founder-driven. From Grab’s Anthony Tan and Tan Hooi Ling to Tokopedia’s William Tanuwijaya, they rode a funding boom fueled by a mobile explosion to create some of the world’s largest tech startups. But they also burned enormous amounts of cash in pursuit of growth. Now that economic uncertainty is squeezing funding and WeWork’s epitomized the perils of placing expansion above profitability, the time has come for corporate mavens to take the reins, some argue.

“It’s the coming-of-age” of Southeast Asia’s tech scene, said Paul Santos, managing partner at Singapore’s Wavemaker Partners. “It’s the end of an era of unbridled ambition and hopefully the beginning of a period of sustainable growth.”

Zaky is only the second founder-CEO to leave a Southeast Asian unicorn, following Gojek’s Nadiem Makarim, who became Indonesia’s education minister. While the former’s departure seemed sudden, it was the culmination of a gradual separation, the people said, asking not to be identified discussing internal matters.

Some of Zaky’s decisions rankled investors. Bukalapak — which means “open a stall” — succeeded by becoming the go-to bazaar for shoppers seeking bargains. But a few years ago, in his zeal to bring more mom-and-pop stores into the network, Zaky pushed too hard for ever-lower prices, disrupting market pricing and upsetting some consumer brands, they said.

Later, as Bukalapak expanded, Zaky grew ambitious and tried to take on rivals like SoftBank-backed Tokopedia and Alibaba Group Holding Ltd.’s Lazada by flogging pricier goods. Bukalapak backtracked when it realized it was getting too far away from its roots. Then in 2019, he incensed followers of popular Indonesian President Joko Widodo after tweeting that the government was spending too little on R&D and suggested a new leader might beef up the budget: #UninstallBukalapak becoming a trending topic on Twitter.

Discussions about a changing of the guard began long before that. Zaky had talked with his board about wanting to pursue his passion of helping young entrepreneurs. But that coincided with increasing pressure for the startup to turn a profit, one reason why it announced 10% job cuts. Directors felt that, while Zaky had been instrumental in Bukalapak’s early days, the company had outgrown him and proposed bringing on an experienced executive. In December, the board appointed a successor in Rachmat Kaimuddin, a former director of finance and planning at PT Bank Bukopin that Zaky himself and a co-founder recommended.

“As startup capital raising and profitability come under pressure, we should expect to see more CEO exits. Not just for under-performance, but for other reasons that were ignored under hyper-growth,” said Suresh Shankar, founder and CEO of Singapore-based Crayon Data. “Travis-like (behavioral), Adam-like (financial engineering) or Moonves (CBS, alleged sexual misbehavior) exits will become more common. Sometimes one of these causes or the other will be used as the excuse, to make company under-performance seem more palatable.”

Unlike Uber’s Travis Kalanick, Adam Neumann of WeWork or CBS’s Leslie Moonves (who denied allegations of impropriety), Zaky leaves Bukalapak with his reputation largely intact. He will remain an adviser to Bukalapak while chairing his own foundation to support startups.

Born in central Java in 1986 to school teachers, Zaky got his first PC (an Intel 486) from his uncle at the age of 10 — the only one in his village. By the time he got to high school, he was competing in national competitions, and eventually enrolled in the prestigious Bandung Institute of Technology. There, he met Nugroho Herucahyono, with whom he started Bukalapak in his dorm room. College friend Fajrin Rasyid left Boston Consulting Group to join them in 2011.

By the end of the first year, they’d run out of money and considered throwing in the towel. Then a chance meeting with Japanese venture capitalist Takeshi Ebihara revived the startup (Zaky tagged along with a friend to a meeting.) To his surprise, Ebihara offered to invest in Bukalapak. He also provided early guidance to the founding team.

One of the lessons was the importance of control. Zaky was cautious about raising too much money to avoid dilution. While Tokopedia and Grab raised billions, Bukalapak raised less than $500 million from investors including PT Elang Mahkota Teknologi, better known as Emtek, Singaporean sovereign fund GIC Pte and Jack Ma’s Ant Financial.

“I want to make sure I have a large stake, like Mark Zuckerberg,” Zaky said in an interview in 2016 at Bukalapak’s offices in Jakarta, decorated with replicas of bird cages to convey the Asian bazaar aesthetic and slogans like “Get Sh*t Done.”

Zaky’s and Nadiem’s exits now presage a trend. “‘It’s not about you’,” Nadiem wrote in his farewell email.

In his own parting memo, Zaky counted professionalizing his company among his achievements. He recounted an incident in its early days when the website went down for days and no one was bothered. By mid-2019, when the company had 2 million mom-and-pop store partners and agents and more than 70 million active users, Bukalapak had executives to run finance, strategy and operations.

“I remember our early years when our management style was still ‘dormitory’ style,” he wrote. “Over time, our management has become more modern.”

Source: https://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2020/02/13/exit-ofindonesias-tech-whiz-kid-is-a-warning-to-startups.html

Thailand

Thailand