Working for change

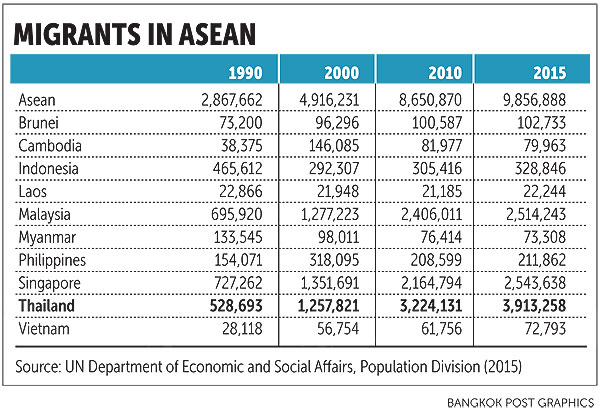

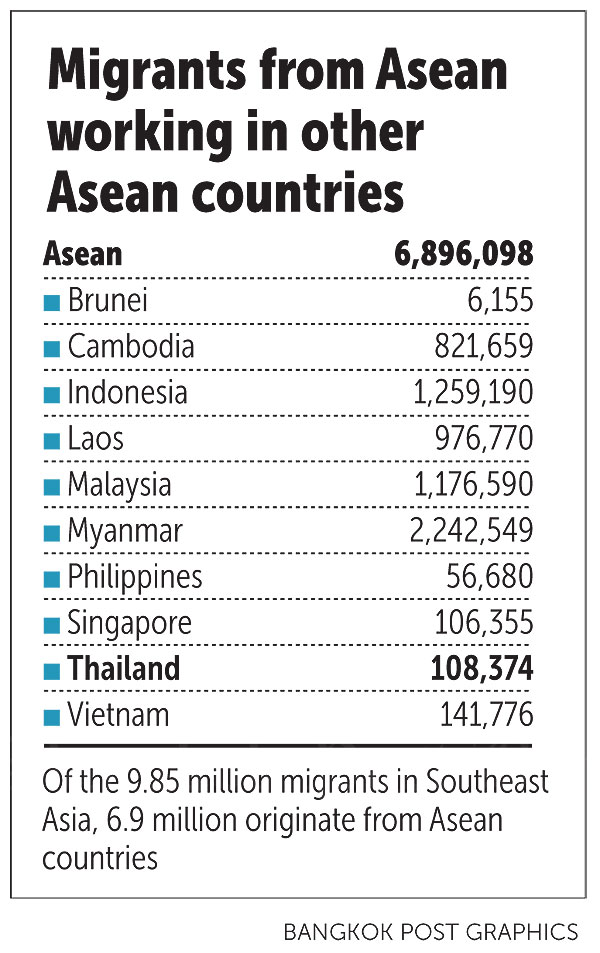

Southeast Asia hosts nearly 10 million migrants, of whom roughly 7 million originate from countries within the region. The main component of migration involves the movement of lower-skilled labour, predominantly from Myanmar, Cambodia and Laos to Thailand.

In Asean and around the world, labour migration has proved to be a force for good, rather than something to block. But its benefits to the region are often forgotten or overlooked, and the difficulties experienced by workers too often neglected.

“You can see how important labour migration has been for some countries,” said Nissara Spence, regional research assistant with the International Organization for Migration (IOM).

Most intra-regional migration involves a steady stream of willing lower-skilled workers who fill gaps in the job markets of host countries, many of which are now focusing on upgrading the skills of their own workers.

Robin Ramcharan, executive director of the Asia Centre, said labour migration in Asean brings economic benefits not only to host countries but also provides a steady stream of income back to workers’ home countries within Asean.

“Broadly speaking, and going back over the last 20 years, I think labour migration has been very important for the economics of Asean,” he told Asia Focus. “The contribution of migrants in general to their host countries is one thing, but then to their home economies it is also quite substantial.”

Workers coming to Thailand from Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar account for 58% of all migration within Asean, Ms Nissara noted. They accept jobs that natives of host countries are no longer willing to do, in construction, fishing, domestic work and other services. “In Singapore alone, 40% of the workforce is made up of migrant workers,” she said.

Ageing populations around the region are further shrinking the pool of available workers, especially in more developed countries, creating more demand for migrants.

“In Thailand, 11% of the population is 65 or over. That’s about 7.5 million people,” she said.

“But in addition to filling labour shortages in host countries, migrant workers also contribute to increasing capital and promoting trade,” Ms Nissara added. “Some may not earn enough to pay tax in the countries of destination, but they are still consumers and spend income on living in that country.”

In addition to spending money on food, rent and clothing in host countries, migrants make major contributions to their home countries through remittances. Around 75% of Myanmar migrants send remittances back home, said Ms Nissara.

“Remittances can be used to reduce poverty back home as well as an indispensable source of income for families in countries of origin,” she said. “These funds are often used for food, education and healthcare for their families.”

Dr Ramcharan agreed, saying remittances in some countries were “quite substantial” reaching as much as 6-7% of gross domestic product in the Philippines, for example.

The construction sector is one of the main employers of hundreds of thousands of migrant labourers in Thailand. Photo: Pattarapong Chatpattarasill

The construction sector is one of the main employers of hundreds of thousands of migrant labourers in Thailand. Photo: Pattarapong Chatpattarasill

ASSOCIATED PROBLEMS

Given how valuable a resource a large, willing and flexible migrant workforce can be, it is disappointing that workers encounter so many difficulties, notably exploitation by recruiters and lack of labour protection.

“Not all migrants are protected under national labour laws. For example, domestic workers often do not have the same protections because the workplace is a private home and outside of the scope of labour inspectors. This equally holds true for those workers who are employed informally,” said Ms Nissara.

Many arrive through irregular channels, without the necessary documents and lacking knowledge about how to access the necessary information. Accordingly, exploitation is not uncommon.

“You potentially could see abusive practices such as withheld pay, or underpayment compared to the minimum wage or compared to what they were told they would be paid,” said Joshua Hart, project officer (labour migration) with the IOM in Thailand. Withholding of documents is common, with many workers too afraid, or unsure how, to seek help out of fear of retribution or arrest and possibly deportation.

This creates an atmosphere of dependency, with many reliant on their employers to access certain services. “Imagine you have come to Thailand and all of your identification — your passport — has been withheld by your employer,” Ms Nissara illustrated. “Additionally, for them then to access healthcare, they will have to rely on employers to take them.”

Some workers are forced to pay off existing or fabricated debts before receiving their passports back. “We really have to regulate this better,” said Dr Ramcharan. “Singapore confronted this early on and I think they have taken measures to be fair and control recruiters and employers.”

These problems are not limited to workers but can also affect heir family members. “For example, sometimes migrant workers bring their families as well. The worker may have access to healthcare but their family members may not,” Ms Nissara explained. “There are still gaps — the protection of migrant workers itself is not fully comprehensive, let alone for the family members who also come.”

Dr Ramcharan said the lack of consistent rules across the region for labour migrants is worrying.

“From the departure stage to the arrival stage for migrants, there are different rules spread out,” he said. “And coming from a classic customary international law, do you have a right to leave your country? Yes you do. But, then do you have a right to enter another? No.”

For that reason, he believes, “a broader normative framework” is needed, especially for undocumented workers, to prevent abuses.

AWARENESS

Raising awareness, both among the wider public about the benefits of labour migration and within the migrant worker community, is essential as Asean becomes more integrated.

Xenophobia, while not widespread, still exists and needs to be addressed, Ms Nissara explained. “In one way, people may believe that migrant workers are coming in take their jobs. But in reality, they complement the market and provide more job opportunities for locals.

“For example, in Thailand and Malaysia, migrant workers come to work in agriculture and actually increase jobs for the local population who are employed in related areas such as food processing, transport and sales.”

Misconceptions and scaremongering about migrants need to be tackled more seriously, Dr Ramcharan agreed.

“Generally speaking, one can never do enough to emphasise how important these people are to any country’s economy,” he said. “They fill the jobs that many locals will not do.”

Previous IOM publications enforce the idea that many people still view migration, and migrant workers, as something to curtail rather than welcome and celebrate. The IOM’s 2015 report, “How the World Views Migrants”, asked respondents whether they wanted migration to decrease, stay the same or increase, and whether people believed that migrants were taking jobs from the local population.

In all of Southeast Asia, 40% of respondents said they wanted migration to decrease, above the global average of 34%. It was the most popular of the three answers.

To help promote inclusion and clarity, the IOM has created the “I am a Migrant” web platform. It showcases stories of migrant workers in the hope of portraying them as workers, parents and friends, rather than simply labour.

For example, Anand, as shown on the website, is a lifting supervisor from India who currently works in Singapore. With two daughters, he works six days a week. Anand has been living and working in Singapore for four years and has “only positive observations of Singapore”.

Labour attaches at consulates, with The Philippines setting a good example at its diplomatic missions, also help raise awareness. In this case however, the focus is on the migrant workers, informing them of their rights and designated provisions.

“The role of the consulate is very important,” Dr Ramcharan said, noting how consulates of The Philippines ensure that labour attaches operating in host countries provide adequate information and help to migrant workers.

Such efforts are intended to safeguard the protection of Philippine nationals working abroad, by doing raising awareness of what services they can access and what rights they have.

By providing legal and welfare assistance, promoting available employment opportunities and helping national governments create and implement better policies toward migrant workers, labour attaches thus play a vital role within the migration sphere.

Migrant workers in the seafood-processing hub of Samut Sakhon show off identification cards issued under a 2014 programme to legalise foreign labourers. Photo: Pattanapong Hirunard

Migrant workers in the seafood-processing hub of Samut Sakhon show off identification cards issued under a 2014 programme to legalise foreign labourers. Photo: Pattanapong Hirunard

Thailand

Thailand