Asean needs to re-think approach to US$2.8tril infrastructure gap

A HUGE infrastructure gap exists in Asean and it has become increasingly clear in recent years that the region may not be able to fund its infrastructure needs.

With the ramping up in demand for infrastructure development, governments in Asean may need to re-look their approach to plugging the infrastructure gap.

According to the Asian Development Bank (ADB), infrastructure investment in Asean from 2016 through 2030 is estimated to be about US$2.8 trillion, which boils down to around US$184bil per year.

Asean countries do not have sufficient public-sector capital to finance all the required projects, according to a Standard Chartered report, titled “Asean – a region facing disruption” which cited a source from ADB, stating that Asean is only able to cover about 50% of the total investment.

The infrastructure gap – the difference in required infrastructure spending and actual investment spending arises as a result of rapid urbanisation and population growth in the region.

Increasing population mobility and communication needs, as well as geographical and environmental factors around trade and sustainability, are also significantly driving demand for infrastructure. Hence, there is a rapid proliferation of infrastructure projects to narrow Asean’s gaping infrastructure deficit.

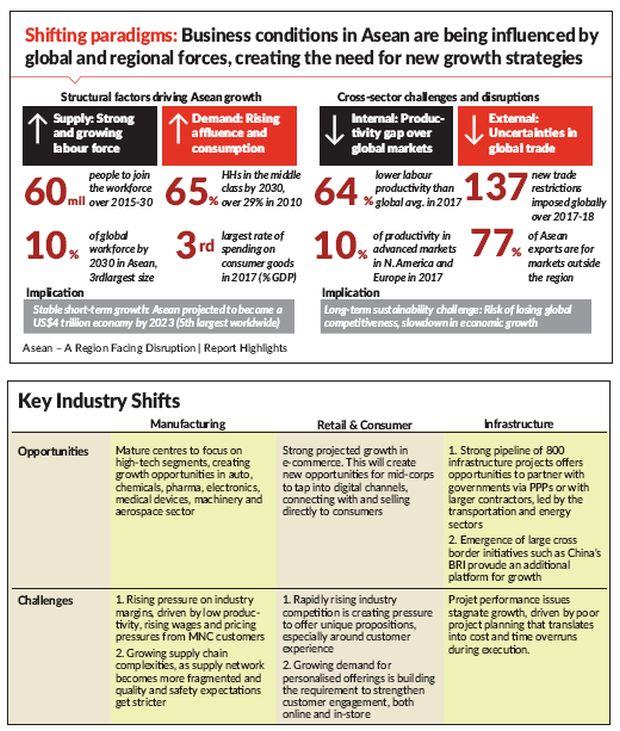

With over 800 projects in the pipeline domestically and cross-border, infrastructure development will continue to contribute to the region’s growth story. Main project areas include transport (473 projects), energy (275 projects including 77 renewable energy projects across hydro, solar, wind, geothermal and biomass), utilities, and social infrastructure.

As demand for infrastructure development soars, the question is how should Asean approach its infrastructure needs?

To be able to identify the right financing approach for each project accordingly, each country needs to set a vision of what its infrastructure needs are in the long term and break it down into near-term plans.

Governments may have begun looking to private sector capital for funding, but finding takers remains a challenge. While private investors are increasingly open to long-term infrastructure investments, ineffective project structuring, gaps in information flows and coordination between private and public sectors, inadvertently keep private sector money at bay.

Supporting regulatory, contractual and risk allocation frameworks are still in development stages in several Asean countries.

The infrastructure industry acts as a key foundation for other sectors to flourish, reducing market inefficiencies that slow down an economy’s pace of development. Effective infrastructure development however, hinges on a well-coordinated approach which calls for close collaborations between governments, multilateral development agencies, institutional investors and commercial banks.

For Malaysia, infrastructure is a high priority area going forward, with plans to increase infrastructure spending in the next few years, especially in sectors such as transportation and logistics, digital connectivity, and utilities – aligned to its target of becoming a high-income economy by 2020-21.

It is estimated that about 85 large-scale projects are currently active in the country, representing a total investment value of US$124bil.

Infrastructure is one of the three sectors that have been identified as a key growth area in Asean, the other two being the retail and consumer and manufacturing sectors.

These three sectors account for 44% of regional GDP, and are expected to maintain strong growth in the near future (7% to 9% annually by 2021).Within these sectors, mid-corporates (companies with annual revenue of between US$10mil and US$500mil) are in a unique position to benefit more.

They have both the capacity to fund innovation and agility to adapt effectively to evolving needs compared to smaller businesses and MNCs.

Sixty million people expected to join the global workforce over 2015-2030, with 10% within the Asean region representing the third largest workforce globally. Rising affluence and consumption will see 65% of households in the middle class by 2030.

Productivity gap is increasingly evident, with 64% lower labour productivity than the global average in 2017. Further, there have been 137 trade restrictions imposed globally from 2017-2018, with 77% of Asean exports for markets outside the region.

To remain competitive, productive and relevant in a region undergoing fast-changing global dynamics and emerging external and internal disruptions, Malaysian mid-corporates need to profitably adapt their business strategies.

There are approximately 10,000 mid-corporates in Malaysia. Despite being just 1% of all Malaysian firms, they collectively contribute about a third of the country’s GDP and employ over 22% of the workforce.

Mid-corporates are in a unique position to drive growth and change as they have a stronger capacity to fund innovation and invest in talent and infrastructure compared with small-scale firms. They are also more familiar with local markets compared to large-scale multinationals.

By enabling a more digitalised journey and new partnerships, mid-corporates can expand into fresh regional markets to trigger their next phase of growth.

Cross-border expansion is one of the key growth strategies identified for mid-corporates going forward, apart from adopting smart operations and digital go-to-market initiatives.

Growth strategies for infrastructure mid-corporates

The emergence of cross-border initiatives, like China’s ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), is also expected to be a catalyst to help Asean countries fulfil their infrastructure gaps across the region.

China is the second largest market for Asean exports and imports with total volume of trade hitting a record high of US$587.87bil in 2018. Initiatives for trade liberalisation, such as the China-Asean Free Trade Area, have also substantially eliminated tariff barriers on goods traded between China and Asean since 2010.

Malaysia was the first Asean country to establish diplomatic ties with China in 1974. Bilateral trade volume 45 years ago between China and Malaysia was only US$159mil.

China has since been Malaysia’s largest trading partner for 10 consecutive years since 2009. By 2018, Malaysia’s trade with China rose by RM313.81bil, constituting 16.7% of Malaysia’s total trade.

To take full advantage of the growth opportunities in Asean, mid-corporates must first focus on upgrading their capabilities to a standard that will allow them to win and appropriately execute projects across the region.

Many mid-corporates in the region are already using or planning to adopt technologies such as Building Information Modelling (BIM) to drive their efficiency and performance.

Other more advanced technologies such as Digital Fabrication techniques including 3D printing, which are expected to gain traction in the longer term, show significant potential to revolutionise areas such as housing construction.

These digital solutions will help improve project planning, enhance performance levels, and reduce cost and time overruns.

Once a regional capability model is established and adapted to the intricacies of a target market, mid-corporates must seek to build synergistic partnerships that will create the right medium for success and provide further opportunities for mutual growth in the long term.

The role of commercial banks in plugging the gap

Commercial banks can provide the missing link in the infrastructure development picture. Not only do these banks have the ability to take on greenfield project risks and provide liquidity, they can also work with governments to create the right conditions for financing, which help in the creation of a sustainable pipeline of bankable projects.

The ability of commercial banks to structure transactions appropriately so that risks sit with the most suitable party, is key to unlocking new sources of capital for infrastructure development.

The money management community, which lacks the appetite for diverse risks generated from projects in their initial phase, is more likely to provide longer-term infrastructure financing if short-term bank loans have been used to fund the early phases of the initiatives.

Multilateral development lenders, such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), can also play a critical and complementary role in Asean’s infrastructure ecosystem. By providing assistance and guarantees, which has the effect of reducing risks, AIIB can make capital projects more attractive to commercial banks and institutional investors.

Similarly, commercial banks can play a leading role in the coordination of regional projects, enabling cross-border projects to take root and bear fruit. Not only will higher-quality infrastructure catalyse trade and investment ties among Asean members, greater physical connectivity will also attract more visitors to the region, increasing consumption and growth.

Infrastructure development is not a silo initiative. It calls for a coordinated approach involving collaborative governments, multilateral development lenders, commercial banks with well-established global networks and expertise in appropriate risk structuring, viable capital markets and cash-flushed institutional investors. And commercial banks are the fabric that binds all these parties together.To find out more about growth opportunities in Asean, visit sc.com/en/banking/Asean

Note: A first of three series of articles by Standard Chartered on the key growth opportunities in Asean

Source: https://www.thestar.com.my/business/business-news/2019/06/20/asean-needs-to-rethink-approach-to-us28tril-infrastructure-gap/#Mhh55PJLsDYkvIXh.99

Thailand

Thailand