Indonesian solar lessons from Vietnam

During the recent Jakarta Car Free Day on 28 July, Indonesia’s Minister of Energy and Mineral Resources, Ignasius Jonan, led a campaign called the National Movement of A Million Solar Roofs (Gerakan Nasional Sejuta Solar Atap) to promote the country’s solar rooftop utilisation.

The campaign is an effort to bolster solar installation as listed in Indonesia’s National Energy Plan (RUEN), which targets solar photovoltaic (PV) installation of 6.5 gigawatt (GW) by 2025 and 45 GW by 2050. However, solar installation in this archipelagic country has been seemingly stagnant over the years, with only 0.1 GW of solar installation (on-grid and off-grid) up to today. This means that Indonesia requires a tremendous effort to add 6.4 GW of solar addition in only six years if they are to meet the target set out in the RUEN. Indeed, there are doubts as to whether it is possible Indonesia can make such a leap.

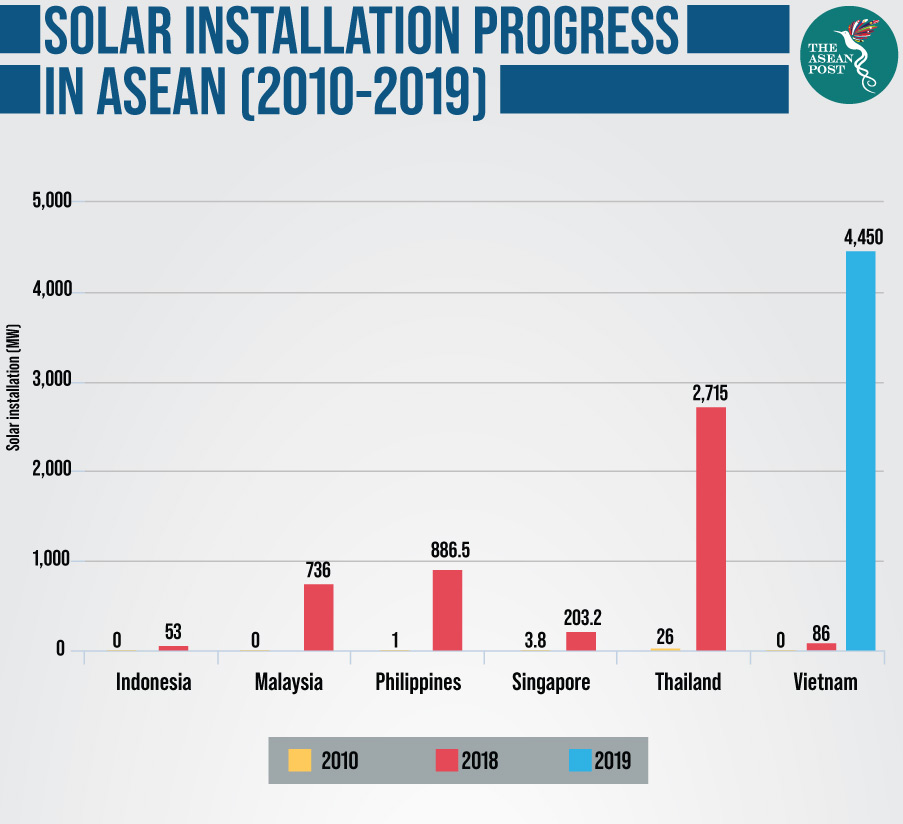

Indonesia’s solar installation is also lagging when compared to neighbouring countries. Based on data from the ASEAN Centre for Energy (ACE), as of June 2019, solar installation across ASEAN is about 9.1 GW – a significant surge from only 0.03 GW in 2010. This growth is contributed by solar installation spurts in Thailand (3 GW), Malaysia (0.7 GW), Philippines (0.8 GW) and recently in Vietnam (4.5 GW) thanks to successful government incentive programmes for renewable energy.

Solar installation growth in these five countries resulted from well-designed incentives for renewable energy, mainly from the Feed-in-Tariff (FiT) system. In all these five countries, solar installation significantly increased after the establishment of FiT. Solar is enjoying a boom in Vietnam, which recorded 4.5 GW as of June 2019 – only two years after FiT was launched. This makes Vietnam the largest solar PV installer in ASEAN, with traditional pioneers Thailand now second.

Source: ASEAN Centre for Energy

Indonesia can take a leaf out of Vietnam’s book after their success in boosting solar energy. Vietnam and Indonesia are rich in coal reserves and still predominantly use coal in their power generation mixes, and both are still developing countries which have high energy demands in response to their economic growth. In addition, Indonesia and Vietnam both have similar electricity market structures under a single buyer model with one state-owned utility – in Indonesia, the State Electricity Company (PLN), and in Vietnam, the Vietnam Electricity (EVN) – as an off-taker. Noting these similarities, it is not impossible for Indonesia to replicate the success of Vietnam in generating more than 4 GW of solar installation in two years.

Price incentive, financial support

Using Vietnam’s success as a reference, there are four key points Indonesia can learn from.

The first is the right solar incentive price setting. Vietnam launched FiT rates for solar at US$0.0935 per kilowatt hour (kWh) in 2017 which was eligible in the first-round for plants that are commissioning no later than June 2019. The solar FiT rates were set higher than the electricity rate in the average retail price – which is at US$0.0803 per kWh – so it incentivises renewable energy developers and attracts investment, but it is also not too high a burden for EVN to pay.

In Indonesia, referring to the cost to PLN of procuring power (commonly referred to by its Indonesian acronym, BPP), the country’s renewable energy pricing, including solar, is capped to the maximum local electricity retail tariff – which is at around US$0.07 per kWh for high electricity demand areas like Java. This does not provide incentives for the generation of solar power since the local electricity tariff reflects the production costs from coal or other fossils.

Since the BPP is composed of the cost of fossil-based generation, this is unattractive for renewable energy developers as renewables are high in this archipelagic region. Learning from other ASEAN pioneers which have succeeded in significant solar PV addition, the government needs to invest in incentives before they can reap the rewards. After that, the government can further help reduce the price of renewable energy when the market is mature. Adjustment of the FiT or an incentivised price will enliven the stagnant solar PV market.

In addition to tariffs, support from the financial sector is important. In Vietnam, the banks and financial sectors are well-aware of solar PV projects, hence they are supportive of the standard power purchase agreement given by the utilities and can provide loans for developers since they see their projects are bankable. A lot of listed lenders for renewable energy projects in Vietnam are from domestic banks, but in Indonesia, the financial sector’s awareness of renewable energy projects leaves a lot of room for improvement. A credit guarantee to the bank is one way the government can support such projects, and capacity building and government facilities to rise these projects’ bankability is another option for Indonesia – in particular among state-owned banks.

Mature local industry

A mature local industry to support the demand of solar is vital. Vietnam has a mature solar manufacturing industry to cater to the high demand when FiT was launched. In Asia, Vietnam is the third-largest solar PV manufacturer with a capacity of 5.2 GW per year in 2016, after India and China.

Prior to FiT, the solar module production was mostly for export, but Vietnam’s manufacturing capacity has prepared the local market for FiT’s establishment. This way, it made sense for developers to use local solar modules rather than imported ones since they provided more economic benefit.

In Indonesia, solar PV production was 416 megawatt (MW) per year in 2017 according to the Association of Solar PV Manufacturers in Indonesia (APAMSI), which makes the local solar module price much more expensive than imported ones. Meanwhile, Indonesia has regulated that a minimum of 40 percent of local products have to be used for renewable energy projects. This certainly creates a burden for renewable energy developers as the prices of local products are still high – which discourages them from investing in renewable energy projects. Learning from this, the government needs to not only incentivise the purchase of electricity from solar, but also support the manufacturing capabilities of local solar manufacturers to increase their production capacity.

PLN buy in, less red tape

Thirdly, Vietnam’s EVN is open and welcoming of solar and renewable energy in their grid system – and have been improving their capabilities to adapt to these technologies. Investment to increase grid flexibility and capacity are required to ensure the intermittency from solar is well-handled, and EVN sees this intermittency as a challenge rather than a threat – hence motivating them to improve their grid capability. EVN also realises that more renewable energy will naturally decrease the intermittency effects as projects can compensate for each other in a large system.

Solar PV and wind are intermittent by nature. Nevertheless, other countries handle this by conducting thorough planning and advanced renewable energy forecasting. As a result, renewable energy penetration will enhance the utility grid system’s reliability instead of depending on fossil generation. Renewable energy will also help PLN to upgrade its monitoring and planning systems, and the capacity building and study of renewable energy grid integration will ultimately help PLN embrace solar PV adoption.

Finally, easing the process of getting permits and support from local government for solar projects are also critical in ensuring rapid solar deployment. In Vietnam, several local authorities in regions where solar potential is high have developed a regional solar roadmap for the region which identifies the allowable places and available capacity for solar developers to submit proposed projects.

Developers no longer have to deal with the lengthy process of getting permits, and in some parts of the region, local authorities even provide their own incentives on top of national incentives – such as land which can be rented by developers. This shortens the time spent on red tape and speeds up the amount of time spent on installation.

Indonesia can support its solar industry stakeholders by transforming the BOOT (build-own-operate-transfer) scheme into a friendlier scheme such as BOO (build-own-operate). Local governments’ participation needs to be improved to create streamlined policies which are in line with the national target and roadmap.

By adopting these four points from Vietnam, Indonesia will likely find it easier to hit their target in six years’ time. Vietnam has provided a very valuable lesson, and Indonesia should have learnt by now that achieving the impossible – installing 6.5 GW in less than six years – is possible if immediate actions and well-designed strategies are put in place.

Aloysius Damar Pranadi and Nadhilah Shani are research analysts under the Policy, Research, and Analytics Programme at the ASEAN Centre for Energy (ACE) in Jakarta. Established in 1999, ACE is an intergovernmental organisation within the ASEAN structure that represents the 10 ASEAN Member States’ (AMS) interests in the energy sector.

Source: https://theaseanpost.com/article/indonesian-solar-lessons-vietnam

Thailand

Thailand