Myanmar: Painful correction

Myanmar’s currency crisis seems to have eased in recent days as a result of government actions, and to the relief of some market observers who feared an Argentina-style meltdown was in the making.

Analysts, however, believe this is only a temporary reprieve as the economic fundamentals that gave rise to the sudden crash remain. If not tackled, the currency crisis could resurface within a few months.

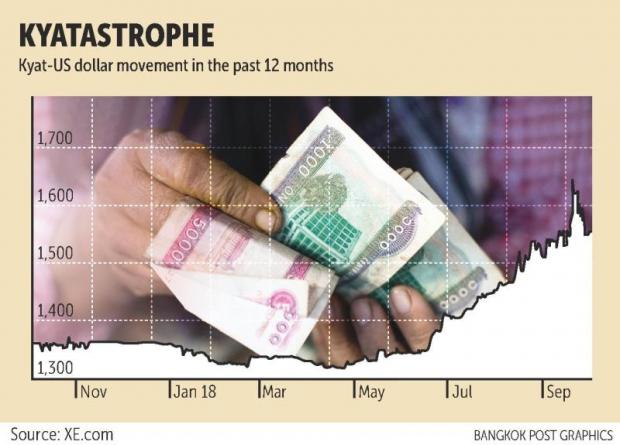

The kyat has depreciated against the US dollar by some 20% over the last three months. In the first week of this month, it recovered slightly and ended in official trading at around 1,540 to the greenback, having sunk to 1,650 two weeks ago.

Analysts said Myanmar’s currency was hit by a “perfect storm” in the last few months and that had made rapid depreciation inevitable. The steady rise of the dollar against currencies worldwide, the country’s growing trade deficit exacerbated by the seasonal dip in export earnings, and rising inflation have all contributed to the depreciation of the local currency.

“The looming potential trade war between China and the US and possible sanctions against Myanmar, have also contributed to the uncertainty on the domestic currency market,” said Vijay Dhayal, managing partner at New Crossroads Asia, a business consultancy and market advisory firm.

Currency speculation — both by local private banks and local currency traders — has compounded the current trend, according to Moe Kyaw, the head of Myanmar Marketing Research and Development Company.

Last week, authorities arrested several local currency and gold traders, accusing them of fraudulent trading intended to force up the price of dollars. This has helped bring the exchange rate down for the time being, Mr Dhayal told Asia Focus.

Unless the government steps up the pace of economic development, especially by investing in infrastructure projects and attracting foreign investment into the manufacturing sector, this improvement will be short-lived, he added.

“The kyat had become irrationally oversold, and over the last week has corrected, with a return of cooler heads,” said Sean Turnell, special economic adviser to the State Counsellor. At the current rate around 1,500, he argued, the rate of depreciation compared to the dollar has been in line with other currency movements in the region, such as the Indian rupee and Indonesian rupiah.

“If we factor in that Myanmar is, in truth, more a ‘frontier’ market than truly an emerging one, with all the risks this entails, then the exchange rate movement was thoroughly unremarkable,” he told Asia Focus.

Nevertheless the impact on the street has been dramatic. The downward spiral of the kyat has taken its toll on the prices of everyday items such as rice, fish, meat and vegetables, eggs, milk and onions. Even salt, which is imported, has risen because of the weaker kyat.

Win Lwin, a Yangon taxi driver, complained that his family budget does not stretch as far any more. The price of rice has risen from 2,000 kyat per pyi (2.1 kilogrammes) to 2,500, and a bunch of watercress now costs around 500 kyat, up from 300. Eggs have gone from 110 to 160 kyat, milk from 2,000 to 2,200 kyat, and the price of onions has doubled, he said.

To make matters worse, the price of petrol has increased by more than 20% in the last four months. This makes it more expensive to drive and customers won’t pay the higher fares, so he earns far less than he did. “It’s difficult to make ends meet now,” he complained.

But for the city’s hapless consumers there is no end in sight. Prices of daily essentials are not going to fall for a while, as the best that can be expected is for the kyat to remain at its current level of 1,540, which sources at the Central Bank of Myanmar predict is the expected equilibrium.

The underlying problem, according to analysts and bankers alike, was that the value of the kyat has been artificially high over the past year and depreciation was long overdue.

“It would have been better if the central bank had managed the currency better by allowing it to depreciate more slowly than the sudden fall over the last three months,” said Mr Dhayal.

Ironically, it appears that the Commerce Ministry may have inadvertently sparked the currency crisis when it decided to allow local businesses to re-export sugar — from Thailand, Vietnam and Brazil — along with Thai diesel to China a few months ago. Sources close to the central bank believe this was a shortsighted move on the part of the ministry.

Although the firms involved in the re-export of these products make a substantial profit — 25% in the case of sugar — it places a strain on the trade deficit and balance of payments. There is a three-month lag between earning the revenue from sales after paying for the imports. And most of the income is in Chinese yuan and not convertible to dollars, so even when the payments are made it does not help the country’s international reserves.

To make matters worse, the decision to allow these re-exports coincided with the rainy season when there is a dip in exports, placing even more pressure on the trade deficit. Sources at the central bank also point to the fact that when the decision was reversed six weeks ago, there was an almost immediate steadying of the exchange rate. But that proved only temporary.

The current currency crisis has unleashed a heated debate about the role of the central bank and its efforts to support the kyat. Most local bankers complained that the central bank did not do enough. “Its laissez faire attitude didn’t help matters,” said Moe Kyaw. “But what could you expect?”

For its part the central bank did take several steps to try to stabilise the kyat: selling millions of dollars from its foreign reserves to local banks, floating the exchange rate and launching a new currency swap facility. But the measures largely proved ineffective.

But Mr Turnell has no doubt that the central bank did the correct thing. “Myanmar’s old fixed exchange rate was for 50 years the most visible symbol of the country’s profound economic dysfunction,” he said.

“A vehicle for rampant corruption and a fictional facade of the country’s circumstances, it was a significant brake on the country’s competitiveness.”

What the bank did was effectively float the kyat and allow the market to establish the rate. Soe Thein, the “economic czar” in the cabinet of former president Thein Sein, strongly rejected the move at the time.

“This government should have continued to fix the rate,” he told Asia Focus recently. But many analysts also believe the central bank had no other option, and that this was the most appropriate move to bolster the local currency in the long run.

“There was not a lot the government could or should have done frankly,” Mr Turnell said. “This story of the kyat slide is, in fact, better characterised as a relentless climb of the US dollar against all emerging market currencies.”

“A stable currency is what the country’s businessmen want above all else,” said Thu Zaw, the CEO of Sithar Coffee, which grows, produces and distributes coffee. “Almost everything is imported, including juices, milk, salt and toothpaste, so fluctuations in the exchange rate make it difficult for businesses to plan, which in the end adversely affects the consumer.”

In practice there is also a limit to what the central bank can do to as it has limited foreign reserves. Unlike other central banks it cannot sell dollars on the currency market to bolster the local currency because it has less than three months’ worth of reserves, according to sources familiar with the situation.

Most analysts and businesspeople in Myanmar put the responsibility for finding long-term solutions clearly at the government’s door. The only way to reduce the trade deficit in the medium and longer term is for the government to promote export industries and import-substitution products. The main solution is to build a manufacturing base, even if raw materials are imported, according to Mr Dhayal.

Myanmar currently imports $600 million worth of vegetable oil from Malaysia and Indonesia; it could be refined and produced locally. Half a billion dollars is spent annually on importing motorbikes from China and Vietnam, when some foreign producers could be encouraged to build a factory locally. Mr Dhayal points to the decline in cement imports, after its peak in 2012-13, after the Thai company Siam Cement built a factory in Myanmar.

“There’s acute lack of leadership on the economy,” said Zaw Naing of Mandalay Technologies. “They should focus on the private sector.”

Businesses want to help but they need to be consulted and involved in the country’s economic planning, he added.

“The government should promote exports by offering incentives,” said Aung Gyi Soe, the secretary-general of the Union of Myanmar Chambers of Commerce and Industries (UMFCCI). “Develop tourism,” he suggested. “It’s a low-hanging fruit that will create jobs and earn foreign currency.”

Some economists, including at the central bank, believe the sudden “currency crisis” reflects weak economic fundamentals and is a wake-up call to the government to get its economic house in better order. But the government’s adviser believes it is already fully aware of the many challenges on the economic front.

“Business sentiment is down, certainly, and political events have had a dampening effect on FDI, but this is both understood and the subject of measures — collectively expressed within the new Myanmar Sustainable Development Plan — that hopefully will turn things around,” Mr Turnell added.

Source: https://www.bangkokpost.com/business/news/1553926/painful-correction

Thailand

Thailand