Asia’s energy challenge

Asia’s rapid development over the past four decades has transformed the region’s stature in the world economy, lifting hundreds of millions of people out of poverty and creating new opportunities for future prosperity.

As the region continues its explosive growth and people continue to migrate to cities at an unprecedented rate, the challenge now is to secure sufficient and affordable energy to keep the economy growing. At the same time, it has become imperative to reduce carbon emissions that are already taking a heavy toll on the environment.

As the region continues its explosive growth and people continue to migrate to cities at an unprecedented rate, the challenge now is to secure sufficient and affordable energy to keep the economy growing. At the same time, it has become imperative to reduce carbon emissions that are already taking a heavy toll on the environment.

The energy market needs a paradigm shift toward greater regional collaboration and integration, with the public and private sectors working together to build appropriate foundations, explore new technologies and energy supply sources, according to business leaders and experts. “Asia has one of the biggest challenges in energy transition because the region has the biggest growth in demand for energy,” Mark Gainsborough, Shell’s executive vice-president of New Energies, told Asia Focus.

Other parts of the world are also shifting to greener energy but they are not challenged by the relentless growth in energy demand seen in Asia. All that new energy needs to be delivered in a more sustainable way, he added.

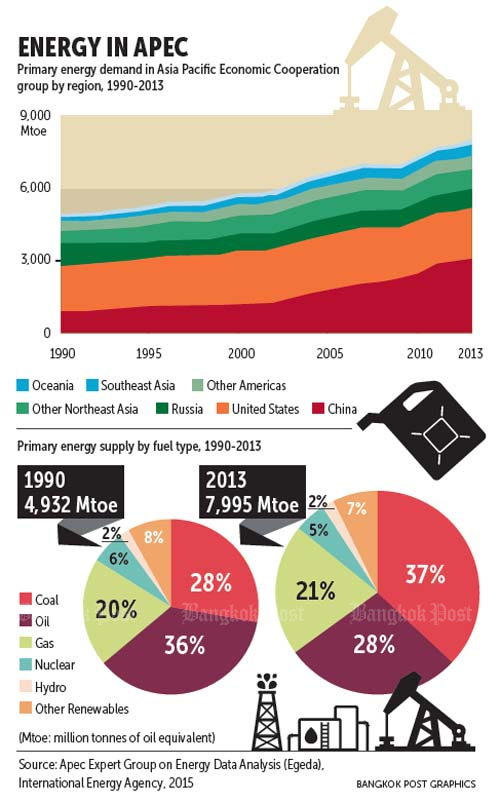

Total final energy demand in the 21 Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (Apec) states is projected to reach 7,000 million tonnes of oil equivalent (Mtoe) in 2040, up 32% from 2013, with China and Southeast Asia the main drivers of growth, according to the Apec Energy Demand and Supply Outlook.

China accounts for more than half of the demand growth owing to its sheer size and continuing growth. In Southeast Asia, the demand will double, reflecting both rapid economic development and low current rates of per capita consumption in countries such as Myanmar.

“Energy is a vital hidden ingredient in almost every economy, with cities the biggest consumers,” said Goh Swee Chen, vice-president for city solutions, new energies and chairwoman of Shell Companies in Singapore. The world needs more energy, but energy that comes with high emissions or a heavy carbon footprint is no longer an option, she told the “Powering Progress Together” forum held in Singapore recently.

Half of the world’s population today lives in cities. Despite occupying less than 2% of the world’s land mass, cities use more than 60% of global energy and the figure is estimated to rise to 80% by 2040.

“Fundamental changes need to happen across the global economy, especially in power, transport, buildings and industry which produce significant carbon dioxide emissions,” said Ms Goh, adding that the pace of change can vary greatly. “Developing countries have the ability to leapfrog ahead and some are already adopting some of the newer energy systems.”

“Fundamental changes need to happen across the global economy, especially in power, transport, buildings and industry which produce significant carbon dioxide emissions,” said Ms Goh, adding that the pace of change can vary greatly. “Developing countries have the ability to leapfrog ahead and some are already adopting some of the newer energy systems.”

By the end of this century, the energy sector will need to be double the size it is today in order to meet the targets of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), according to Mallika Ishwaran, senior economist and policy adviser for Shell Scenarios.

The SDGs are a collection of 17 interrelated global goals covering a broad range of social and economic development issues including poverty, hunger, health, education, climate change, gender equality, water, sanitation, energy, environment and social justice.

“That exemplifies the challenge we have today, which is how you provide more energy but cleaner energy,” she said. “It’s not only about changing the supplies of energy. It’s also about changing how energy is used.”

The world needs a different mix of energy to meet demand while ensuring reduced impact on the environment. But Ms Ishwaran has observed that large energy- consuming sectors of the economy — construction, industry, transport and power generation — use differing approaches to meeting the challenges.

“Each of them has different technology solutions and policy enablers that drive the changes in each particular sector. The challenge is getting the policy coordination to integrate this into the power system today,” she said.

The drive to de-carbonise is more difficult in some sectors than in others, she said. In the industrial sector, for example, many operators have underdeveloped technologies but some governments are not pushing change as much as they could because it doesn’t directly affect the competitiveness of domestic economies.

MORE AMBITIOUS TARGETS

What Asia needs, speakers at the forum said, is enhanced collaboration and a multidisciplinary approach across sectors to set more ambitious targets, implement policies and accelerate energy efficiency. Most of the energy infrastructure in Asia Pacific, they observed, is still publicly owned as the private

sector is either unwilling or unable to take on certain risks in emerging economies. “Collaboration is the only way forward,” said Nathan Subramaniam, director of the Sector and Projects Division, Independent Evaluation Department, at the Asian Development Bank (ADB).

sector is either unwilling or unable to take on certain risks in emerging economies. “Collaboration is the only way forward,” said Nathan Subramaniam, director of the Sector and Projects Division, Independent Evaluation Department, at the Asian Development Bank (ADB).

“We have no other choice but to work toward that and establish the fundamental building blocks to which the private sector can add on.”

The ADB had spent nearly US$2.5 billion over the past decade to help countries undertake public-sector reforms to build more competitive energy markets that the private sector can enter with less risk. The programme includes the development of energy master plans, financial reporting transparency and competitive bidding according to international standards.

Shell’s Mr Gainsborough stressed the importance of government working with all stakeholders — from academics to businesses to civil society — before making crucial decisions. Governments need to think about how they can best encourage the adoption of good, sustainable solutions if they want to see a better energy future.

“They should be open-minded about which technology can help them achieve their goals,” he said. “Sometimes, people are very quick to pick up a particular ‘winner’ because it sounds like a sexy solution, but it may not be the right solution.” When the market is liberalised, he said, it should be allowed to have a go at solving problems. It is sometimes better than a very inflexible market where the government tries to decide for itself which solutions are best.

To encourage the private sector to take part, Mr Gainsborough says there must be the right investment signals. “[Policymakers] need to think about how to structure the opportunities in a way which gives a return to private capital and attracts them to make the investment in infrastructure.”

URBAN SOLUTIONS

For any energy policy to be successful in Asia, it has to reflect the huge influence of urbanisation. The urban population of the world has grown rapidly, from 746 million in 1950 to 3.9 billion in 2014. Asia, despite its lower level of urbanisation, is home to 53% of the world’s urban population, according to a UN report.

By 2050, 2.5 billion more people are expected to join the world’s urban population, with nearly 90% of the increase in energy demand concentrated in Asia and Africa.

“Cities are going to be the important part when it comes to decarbonising and energy transition. Right now about 66% of energy consumed is in the cities. And that is expected to increase about 80% by the middle of the century,” Shell’s Ms Ishwaran pointed out.

To deliver a smooth energy transition to serve urban development, she said, governments should establish a level playing field between different types of energy sources and use them in ways that respect the environment. Consumers should also take the proactive role in demanding the kind of energy that supports the transition.

To deliver a smooth energy transition to serve urban development, she said, governments should establish a level playing field between different types of energy sources and use them in ways that respect the environment. Consumers should also take the proactive role in demanding the kind of energy that supports the transition.

Much of the public debate revolves around sustainable development, clean energy, carbon emission reductions and most importantly, the usage of newer and greener technologies.

But Dr Cheong Koon Hean, CEO of the Housing and Development Board of Singapore, noted that technology is only one element to solve the energy challenge associated with urban development.

The most crucial component of sustainable urban development, she said, is to set strategies and make strategic choices when it comes to urban planning.

“It’s about the policy and plans that set the framework. Technology can come in as an enabler,” she said, adding that sustainability can only be achieved when a comprehensive and holistic approach is taken — starting with strategic planning choices on how to optimise land and resources, and develop in an environmentally responsible manner.

Technology is also very costly. Sometimes, passive design can achieve impressive goals at lower cost. In Singapore, for instance, buildings are designed to minimise the use of energy with natural wind flows and air ventilation. “It’s not necessarily just about the technology, it’s back to good old-fashioned design principles and that’s the starting point,” she added.

Developing countries have the potential to leapfrog ahead by adopting newer energy systems, says Goh Swee Chen, chairwoman of Shell Companies in Singapore. Norman Ng/AP Images for Shell

Governments “should be open-minded about which technology can help them achieve their goals”, says Mark Gainsborough, executive vice-president for new energies at Shell. Norman Ng/AP Images for Shell

Source: https://www.bangkokpost.com/business/news/1435210/asias-energy-challenge

Thailand

Thailand