Asia-Pacific may not follow Fed tightening rate

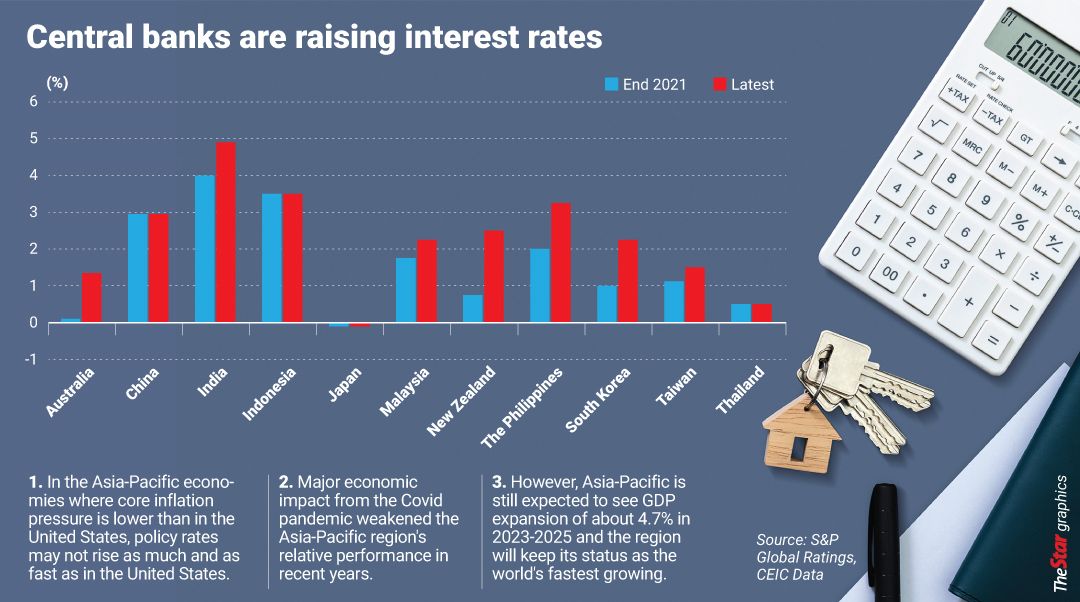

PETALING JAYA: With core inflation in Asia-Pacific not as high as in the United States and Europe, some countries in the region may not need to closely follow the US Federal Reserve’s (Fed) tightening cycle, says S&P Global Ratings.

Core inflation is the price change of goods and services minus food and energy.

The rating agency’s Asia-Pacific chief economist Louis Kuijs said while energy and commodity price hikes have been important in kick-starting inflation globally, it is core inflation that is crucial for inflation prospects in the coming 18 months.

“Rising core inflation in key economies distinguishes this episode from previous energy/commodity spikes, and is what’s prodding central banks to rapidly lift rates,” he added in a report titled “Asia-Pacific: Varying Core Inflation Paths Drive Monetary Policy Divergence” which was released yesterday.

However, Kuijs believes Asia-Pacific may not follow the Fed closely, given the region’s core inflation is generally lower, even in the developing economies.

This has important implications for monetary policy prospects and, possibly, currencies, he added.

Although inflation in the Asia-Pacific region was not as high as in the United States and Europe, the rating agency noted it had risen.

“The weighted average of the 14 economies we cover in Asia-Pacific reached 3.9% in mid- 2022, from 2.5% at end-2021.

“Consumer inflation exceeds (upper bounds of) central bank targets in Australia, India, Japan, New Zealand, the Philippines, South Korea and Thailand,” added S&P.

The agency said the rise in core inflation in the United States started in the spring of 2021, at a time that the economy began to recover from Covid-19 lockdowns and the impact of major fiscal stimulus kicked in.

With little slack in the economy and low unemployment, core inflation had increased steadily since then, and rose to around 6% by mid-2022.

“The Fed seems to have been slow in acknowledging the high level of core inflation.

“With a lag, it has turned more hawkish in order to reduce domestic demand to contain pass-through and wage rises,” said the rating agency, which now expects the Fed to raise the federal funds rate above 3.5% by mid-2023.

Locally, Bank Negara had raised the overnight policy rate (OPR) by 25 basis points (bps) to 2.25% on July 6 – the second interest rate hike this year.

AmBank’s group chief economist Anthony Dass expects the country’s central bank to increase the OPR by 25 bps during both its September and November meetings.

Notably, Dass in a July 25 report noted that Malaysia’s core inflation rose 3% year-on-year (y-o-y), which was the steepest pace since 2017, and faster than 2.4% in May.

The June consumer price index (CPI) grew 3.4% y-o-y, which was also faster than May’s growth level of 2.8% and market expectation of 3.1%, said AmBank.

Meanwhile, S&P noted that in most Asia-Pacific economies, energy and food inflation was relatively modest, in part because of government policies such as administrative price-setting.

“Also, international prices of energy and other commodities don’t continue to rise forever – they will stop rising eventually. Indeed, most commodity prices have started falling since June.

“Most importantly, if such ‘cost-push’ price rises don’t lead to significant increases in inflation expectations and core inflation, the price pressure passes without raising CPI inflation for more than a transitory period, if at all,” it said.

Under such circumstances, credible central banks can “see through” the energy and commodity price hikes and refrain from tightening policy, added S&P.

This is what happened during previous episodes with surging energy and commodity prices such as 2007-2008 and 2011-2014.

“CPI inflation then didn’t rise much in developed economies and once the higher oil and commodity prices had worked their way through the system, CPI inflation returned to the low rates it had been at before.

“Meanwhile, central banks left policy rates unchanged,” it said.

Source: https://www.thestar.com.my/business/business-news/2022/07/27/asia-pacific-may-not-follow-fed-tightening-rate

English

English