A low-key meeting in 1991 gave rise to the ASEAN Free Trade Area

BANGKOK — To this day, when Thai schoolchildren learn by rote the main achievements of their past prime ministers, they are taught that Anand Panyarachun was responsible for the creation of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations’ Free Trade Area (AFTA). What this might mean to them is unclear, but its echoes are still being felt.

In late 2015, ASEAN took another step toward regional economic integration with the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC). With no prospect of political or monetary union, the AEC falls short of the European Union model, which it has never aspired to emulate. Nevertheless, it is grounded in AFTA and the work of Anand and other pragmatic economic liberals in the 1980s and 1990s.

The seeds laid by Anand and others may yet give rise to the birth of the world’s largest trade deal. Early next week in Singapore, ASEAN ministers and leaders will meet with counterparts from six Asia-Pacific nations including China, India and Japan to potentially sign the agreement known as the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership.

The author’s book on Anand’s life is being published later this month. Below are abridged excerpts that describe the former Thai prime minister’s role in creating AFTA:

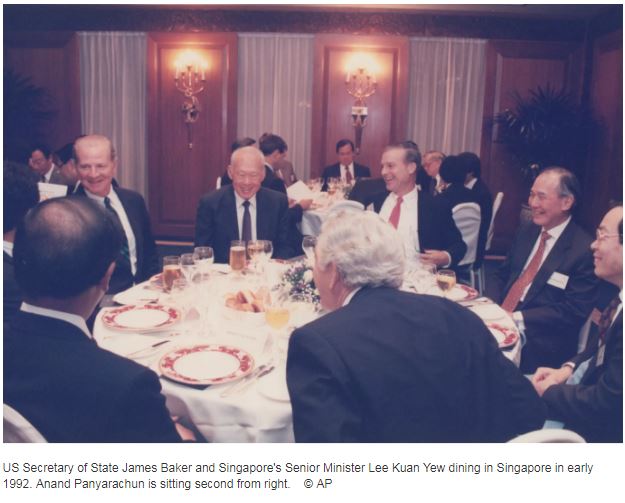

In 1991, Anand was Thailand’s unelected prime minister following a coup in February. During a two-day visit to Singapore in late May, his host was Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong, who had only come into office in November. Goh had replaced the Republic of Singapore’s founding prime minister, Lee Kuan Yew, who now occupied the newly created post of senior minister.

Lee was on the list of people to see Anand during his visit. “You are now prime minister,” Lee told Anand, whom he had known as junior diplomat in the 1960s. “I am just a senior minister — it is I who has to come and call on you.”

As one of the world’s most astute geopolitical observers, Lee arrived in Anand’s hotel suite to discuss matters of mutual significance, including Cambodia. Another, broader, topic was regional trade. Singapore’s march up the world’s economic ranks was (and is) based on its astute development as a trading entrepot, a transport and shipping hub, and as an increasingly high-tech manufacturing center, and regional financial capital, as well as its attractiveness to highly qualified expatriates. Promoting trade and economic relations was therefore core to Singapore’s vision for ASEAN.

Lee knew that among many quasi-public roles in the 1980s, Anand had chaired the Task Force on ASEAN Co-operation in 1984-5 with a view to charting the future course of ASEAN economic relations. Its recommendations had been presented at the ASEAN Summit in Manila in 1987. That was a chaotic period in the Philippines: President Corazon Aquino had been swept into office with the 1986 People Power Revolution after her predecessor, Ferdinand Marcos, had been forced abroad.

The task force’s recommendations had been met with caution by Indonesia. Brunei, Malaysia, Singapore, and Thailand were receptive enough, but implementation posed challenges, particularly in terms of inter-ministry frictions. “They accepted the recommendations with a pinch of salt, but nothing was done subsequently,” Anand recalled. “I knew the timing was not right.”

Lee had liked Anand’s report and proposal, and now saw an opportunity to revive the AFTA agenda. “For the first time in the history of ASEAN, we have a prime minister who has had a career in the bureaucracy and spent some time in the private sector,” Lee told Anand. “In my view, you have another chance.”

Lee spent 90 minutes in the suite before Anand escorted him to his car to see him off personally. They never met formally again. Strategically, Lee and Anand both knew AFTA could not be promoted as any sort of Singaporean initiative. “If Indonesia and Malaysia had known the idea was discussed at my meeting with Lee Kuan Yew, it would have been a problem and treated with a degree of skepticism,” said Anand. Indonesia felt it should always take a leading role in ASEAN affairs, which is one of the reasons the grouping’s secretariat had been established in Jakarta in 1975. Meanwhile Malaysia has always been suspicious of anything with Singaporean fingerprints on it.

Lee was circumspect about his meeting with Anand. “He understood the economics of trade and investment in an interdependent world,” Lee later wrote. “To avoid lingering suspicions about Singapore’s motives, I advised Prime Minister Goh to get Anand to take the lead to push for an ASEAN Free Trade Area.”

Geographically, Thailand was not one of Singapore’s immediate neighbors, and posed no geopolitical or significant economic threat. Indeed, it competed weakly in areas where, arguably, it should have had natural advantages. Japanese and Western multinationals found Singapore a far more efficient environment in which to headquarter regional activities, and Bangkok always came an expensive second to Singapore as an aviation hub for Southeast Asia.

Before ASEAN’s formation in 1967, Lee once admitted to a Thai diplomat that the prospect of a canal across Thailand’s Kra Isthmus, in the mold of Suez or Panama, actually woke him up at night. It would have diverted shipping from the congested Strait of Malacca, and have enormously undermined Singapore’s principal natural advantage – its location at a maritime crossroads. Thailand has never built the Kra Canal, although the possibility is revisited from time to time.

The rate of development in regional trade was always dictated by Indonesia – the world’s fourth most populous nation, which to this day accounts for 40 percent of the combined ASEAN economy. Indonesia during the early 1990s was still a very closed economy and protective of its industries; but without its involvement there was no point talking about ASEAN free trade.

The imperatives in 1991 were stronger than in 1987 when AFTA had failed to gain traction in Manila. The Uruguay Round of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) was taking multilateral trade negotiations into new areas, including agriculture, services, textiles, and intellectual property; a final draft text was delivered in December 1991. Canada, Mexico, and the U.S. were pushing ahead with the North America Free Trade Area (NAFTA). New markets were emerging in Eastern Europe, and the Single European Market was consolidating itself, bolstered by the reunification of Germany in 1990. Closer to home, ASEAN was directly involved with emerging multilateral economic structures, including Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC).

Singapore had become in some ways as a think tank for ASEAN. But for all the intellectual brilliance Lee and his cabinets brought to the table, it lacked the geopolitical clout to set regional agendas. With its free economy and liberal tax system, it was also often regarded by other ASEAN members as suspiciously ‘Western’.

In terms of political protection and economic survival, Singapore probably had the most to gain from AFTA, but it could not afford to be seen as AFTA’s leading advocate. That is where Thailand came in. Dispassionate and removed, the second largest economy in ASEAN, Thailand often proved Singapore’s vital, quiet ally. In many ways, the encounter between Lee and Anand in the hotel suite was a crystallization of that relationship.

Once Lee reseeded the AFTA initiative in his mind, Anand formed a working group to move it along. Anand’s most important selection, his point man, was Narongchai Akrasanee, a Thammasat University economist who had worked with him on the ASEAN task force. Naronghai’s influences included Professor Seiji Naya, the Japanese-American chief economist at the Asian Development Bank (ADB). Naya was a powerful proponent of economic cooperation in Asia, including ASEAN, and chaired a pioneering joint study on ASEAN free trade that Narongchai helped write up in Manila. The Philippine capital was the location of the headquarters of the ADB, backed principally by Japan and the U.S.

Anand’s AFTA initiative gathered momentum. At the 24th ASEAN ministerial meeting in Kuala Lumpur in July 1991, the final joint communique noted the advocacy by Thailand supported by Malaysia of establishing AFTA. Anand visited Indonesia twice to broach the subject with a dubious President Suharto. He was accessible and friendly enough, but his reaction on Anand’s first visit was not that positive. “He did not say yes or no, but definitely he was not too happy,” Anand recalled.

Some believe that Indonesia increasingly viewed China’s economic rise as a threat to its foreign investment prospects, and felt it had no choice but to open up. “The actual agreement to the proposal by Suharto was given to me on my second visit,” Anand recalled. “I did not ask him what changed his mind… He always had his suspicions about Singapore, and knew that Indonesia was not at the same level of development with it, or with Thailand and Malaysia, and possibly even the Philippines. I made it clear that we would take that concern into account, and that we would not run as fast as the most developed country – Singapore – might want. I also impressed on him that this project could not fly if Indonesia did not come on board.”

“Eventually, we offered the 20-year transition period in order to get the Indonesians to go along. I did not have an actual time frame in mind – just as soon as practicable,” said Anand. At a later meeting in Chiang Mai, it was the Indonesians who could see more clearly the practical benefits of AFTA, and they pressed to actually speed up the process.

AFTA was formally endorsed on 28 January 1992, at the fourth ASEAN summit held, appropriately enough, in Singapore. The host, Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong, was of course strongly supportive, his views being consonant with those of Lee. ASEAN declared it was moving towards “a higher plane of political and economic cooperation.”

Abridged from ‘Anand Panyarachun and the Making of Modern Thailand’ (p.264-73) by Dominic Faulder. Published by Editions Didier Millet, Singapore, November 2018.

Source: https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/International-Relations/A-low-key-meeting-in-1991-gave-rise-to-the-ASEAN-Free-Trade-Area

English

English