Thailand: Avoiding a debt meltdown

With a recession creeping on the horizon as business activity and the economy as a whole are ravaged by the coronavirus pandemic, financial authorities have coordinated their efforts to launch a raft of relief measures for those under strain.

The Finance Ministry and the Bank of Thailand last Tuesday announced a third batch of relief measures totalling 1.9 trillion baht — dramatically larger than the tally of the first two packages worth 400 billion baht in total and the country’s largest-ever budget used for economic remedies — to soften the economic blow of the outbreak and avert a debt meltdown.

To offer the massive relief measures, three royal decrees were dispatched.

The first decree will allow the government to borrow 1 trillion baht, of which 600 billion baht will go to health-related plans and financial aid to those whose jobs and businesses have been upended in the virus outbreak. The remaining 400 billion baht will go to economic and social rehabilitation through projects aimed at creating jobs, strengthening communities and building infrastructure.

The second decree will allow the Bank of Thailand to offer 500 billion baht in soft loans with a 2% annual interest rate to small and medium-sized enterprises, with a credit line of no more than 500 million each.

The third decree enables the central bank to set up a 400-billion-baht Corporate Bond Stabilisation Fund (BSF) tasked with buying investment-grade bonds from companies that are unable to fully roll over their bonds maturing during 2020-21.

The three decrees, however, have raised concerns that the country’s public debt could swell to the point of hitting the ceiling of 60% of GDP set by the Finance Ministry’s fiscal sustainability framework.

Some also argue that the planned corporate bond purchases go beyond the central bank’s duty and any damage could come at a cost to the public.

Massive borrowing

Public debt is estimated to touch 57% of the country’s GDP in the next fiscal year after taking into account the 1 trillion baht in borrowing and a 600-billion-baht budget deficit for fiscal 2021, said Patricia Mongkhonvanit, director-general of the Public Debt Management Office.

A peak of 59.9% occurred during the 1997 financial crisis, she said.

Public debt amounted to 7.03 trillion baht at the end of February, representing 41.4% of GDP.

The 1 trillion baht in borrowing also does not surpass other fiscal security criteria, Mrs Patricia said.

Debt principal repayment, for instance, will be 21.2% of annual budget expenditure in fiscal 2021, while interest payment accounts for 7.4% of state income. Both are below the ceiling set at 35% and 10%, respectively.

Setting the threshold at 60% of GDP for public debt appears to be a tough framework, Mrs Patricia said, and the level that exceeds the ceiling does not mean that government lacks fiscal discipline when compared with other countries.

Take Singapore as a prime example. The city-state’s public debt represented 112% of GDP in 2018.

In Singapore’s case, its outstanding debt comprises Singapore Government Securities, Special Singapore Government Securities and Singapore Saving Bonds, which the government does not issue to spend but instead invests all the borrowing proceeds, with these borrowings backed by assets.

As the Singapore government’s assets outweigh its debts, the country has a net debt-to-GDP ratio of 0%.

Finance Minister Uttama Savanayana said the borrowing size is justified because the disease-induced crisis has a wide impact, from grassroots people to large corporations.

Kla Party leader and former finance minister Korn Chatikavanij said he agreed with the 600 billion baht in borrowing to help virus-ravaged people and farmers and for public health, but it must be spent in a transparent and fair manner.

For the 400 billion baht in borrowing to be used for economic and social rehabilitation, he disagreed with issuing a royal decree to finance the proposal, as the executive decree on borrowing is normally used in case of emergency.

The government should allocate 400 billion baht from the 2021 annual budget, he said, as the next fiscal year will start in October 2020.

“The government should preserve its ammunition and avoid being criticised as exploiting an opportunity,” he said.

Mr Korn also voiced concerns about the swelling public debt and how this could offset the economic recovery.

An activist lawyer holds placards calling for Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha’s help in obtaining a debt moratorium from commercial banks. Apichart Jinakul

An activist lawyer holds placards calling for Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha’s help in obtaining a debt moratorium from commercial banks. Apichart Jinakul

Corporate bond buying

Former finance minister Thirachai Phuvanatnaranubala posted a letter written to Khem Yenying (an alias used by former central bank governor Puey Ungphakorn when he joined the Free Thai Movement during World War II) on his Facebook page that said the Bank of Thailand should not play a role as a banker for companies and judge which companies deserve assistance.

“The BoT should be an island in the ocean, which is the country’s risk-free pillar, even in the midst of storms,” he said.

He agreed with former deputy prime minister Veerabongsa Ramakura that investment-grade bonds today could be junk bonds in the next three months amid the global Covid-19 crisis.

“I view that the royal decree (to authorise the central bank to buy corporate bonds) is beyond the central bank’s duty stipulated in the Bank of Thailand Act,” Mr Thirachai said. “The most concerned issue is that when the royal decree that distorts the central bank’s duty and role can be issued once, it could happen again in the future and it is unpredictable how bigger a mess will be.”

The central bank’s corporate bond purchase plan is not quantitative easing as implemented by many countries, where they have bought bonds from only secondary markets under an open market process, he said. The bank will buy corporate bonds on the primary market.

According to the royal decree, the Bank of Thailand will be allowed to buy investment-grade corporate bonds to the tune of 400 billion baht through the BSF, which has a lifespan of up to five years, and the government’s loss compensation will be capped at 40 billion baht.

Two committees will also be formed, one chaired by the finance permanent secretary to make decisions on policy issues and another chaired by the deputy governor of the central bank to pick which bonds will be purchased.

The Bank of Thailand should take care of bond markets through commercial banks, specialised financial institutions and insurance companies by allowing them to buy bonds, which can be used to back loans from the central bank, Mr Thirachai suggested, adding that the central bank can repurchase these bonds at the rate of up to 95% of the purchased prices.

Mr Korn said the central bank is required to set a mechanism that can reflect actual bond prices and needs to set out that corporate bond issues must seek 50% of the funding needs by themselves.

Central bank governor Veerathai Santiprabhob said it’s necessary for the central bank to take a precautionary measure to ensure that the bond market will function normally and corporations will not experience a liquidity crunch, as the total outstanding in the Thai corporate bond market amounts to 3.6 trillion baht, representing more than 20% of the country’s GDP.

The move is also to assure that some vulnerabilities will not become too profound to a point of deteriorating the country’s financial stability, Mr Veerathai said.

The issuance of a emergency decree authorising action on the BFS is not an amendment to the the central bank’s law, but rather a temporary action. The decree’s duration is five years and does not change the principles laid down in the Bank of Thailand Act of 2008.

The central bank is still adhering to the principle of being a last-resort lender for short-term reserves to companies with viable business performance.

Pre-empting a potential failure of corporate bond rollovers, the central bank will buy high-quality bonds from issuers that manage to raise the majority of their funding needs through other means such as bank loans or capital increase, have a clear long-term financing plan, and meet other conditions set out by the BSF’s investment committee later.

Vachira Arromdee, an assistant governor, said the BSF is an unprecedented mechanism that lets the central bank directly buy corporate bonds and is a pre-emptive measure to curb bond market risks.

“It’s a cushion,” she said. “It’s a pre-emptive measure that allows us to take care of it since the beginning, unlike the 1997 financial crisis. We have prepared tool kits which are ready for implementation as the problem is looming.”

Bangkok’s central business district on the evening of April 3, the first day of the 10pm-4am curfew in the capital. Pattarapong Chatpattarasill

Bangkok’s central business district on the evening of April 3, the first day of the 10pm-4am curfew in the capital. Pattarapong Chatpattarasill

‘Negative sign’

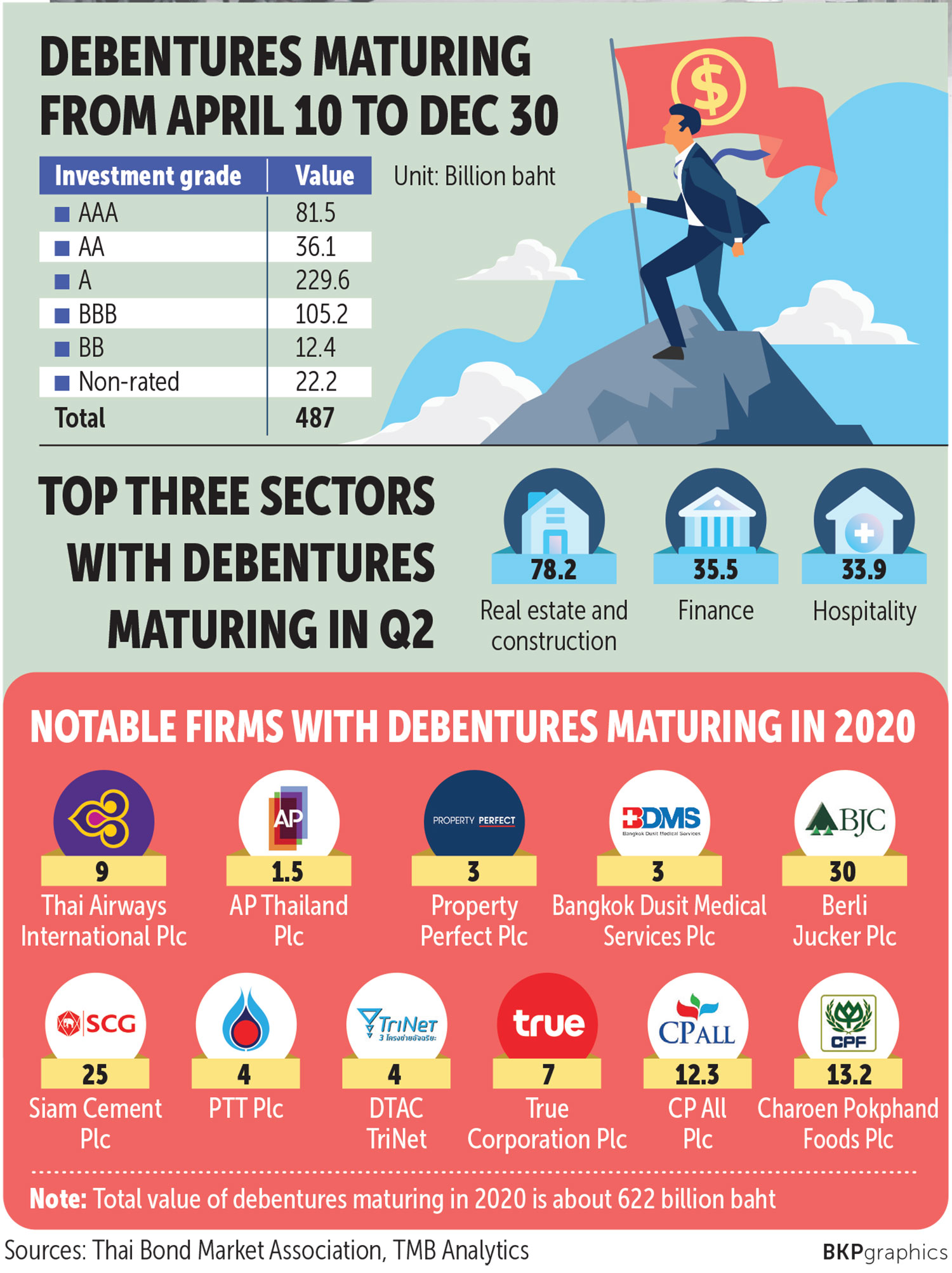

The total value of debentures maturing in 2020 is about 622 billion baht, according to data from the Thai Bond Market Association.

TBMA president Tada Phutthitada said the measure to support corporate bonds would be enough for those maturing this year.

Among the conditions to receive support via the BSF, only investment-grade bonds, whose credit ratings must be above BBB-, will be eligible for the liquidity assistance.

“However, it is believed that corporates can borrow from banks, but banks would request collateral assets for loans,” Mr Tada said.

A fixed-income industry source said the central bank is now supporting corporate bond issuers in order to provide liquidity for them during irregular market conditions.

However, there are about 40 billion baht worth of non-rated and high-yield bonds set to mature this year that will not be eligible for the assistance.

These issuers will have to borrow from financial institutions to close their projects if they cannot roll over, the source said.

In case of a failure to borrow, there is the chance of defaulting on bond payment.

Most high-yield bonds have been provided by intermediary companies, such as securities firms, for high-net-worth investors. No mutual funds are investing in these bonds at the moment.

In March alone, fund outflows from short- and medium-term corporate bonds totalled about 400 billion baht. Of the total, 80 billion baht was shifted to invest in money market funds and the rest went to bank deposits.

“This is a negative sign signalling rollover difficulty of corporate bonds,” the source said.

Surviving together

To let SMEs in dire need of liquidity access the 500 billion baht in soft loans, the central bank must instruct banks not to extend the low-rate loans only to their prime customers.

The central bank should identify in detail the qualifications for soft loan borrowers, said Piti Tanthakasem, chief executive of TMB-Thanachart Bank.

It’s normal practice for banks to focus on their existing customers, given that they already have these clients’ data for credit risk analysis, Mr Piti said.

Good risk management is crucial, particularly in a period of crisis to control risks and maintain overall financial stability, he said.

But it’s quite difficult to analyse credit risk even of existing customers during the coronavirus upheaval.

“Banks want to help all customers to survive, as it’s also a means for banks to survive together,” Mr Piti said. “Offering loans to existing customers helps banks better control risks.”

Apart from the soft loans, TMB-TBank offers an additional credit line to support business liquidity on a case-by-case basis to its customers, he said, adding that the bank finances pandemic-hit businesses even for wages to help them keep their employees and contain economic risks.

Source: https://www.bangkokpost.com/business/1898590/avoiding-a-debt-meltdown

English

English