Showing our age

The Asia-Pacific region is “ageing at an unprecedented pace”, with developing facing bigger ageing challenges than developed ones, the United Nations has warned. Given their limited healthcare and pension budgets, developing countries in particular need to look for more innovative ways to improve the quality of life of their senior citizens. Tapping new technology could be part of the solution.

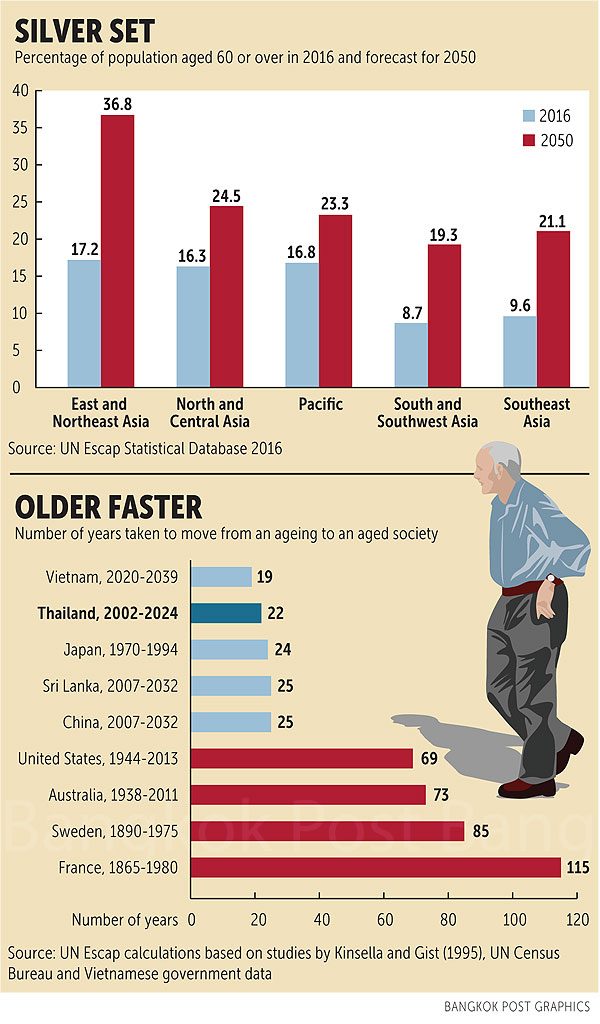

Nearly 80% of the world’s population will live in less developed regions by 2050, according to the “Ageing in Asia and the Pacific: Overview” report by the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (Escap). In East and North Asia, 37% of the population will be aged 60 or older by that time, compared with just 24.5% in North and Central Asia. In Southeast Asia, 21% of the population will 60-plus in 2050 compared with 9.6% in 2016.

Helping people plan financially for retirement is one crucial area that needs improving, according to the “Asia Retirement Income” report by Milliman, a global provider of actuarial data. “A large part of the population currently does not use financial advice and most would benefit from it,” it said.

Milliman surveyed more than 100 insurance companies and financial institutions across Asia and found that 63% of respondents identified the cost of financial advice as one of the “key impediments” to broader use.

“Without proper disclosure, costs are usually completely opaque to consumers, or at least not well understood, under commission-based distribution models,” it said.

Lack of knowledge and lack of trust in companies offering financial advice were also cited as the key barriers. Meanwhile, too many people cling to the notion that their governments will not abandon them during retirement, so they do little planning themselves.

“In many cases, individuals do not start planning for retirement until midway through their careers, when many reach the height of their earning potential. For example, in Singapore, the average age to start planning for retirement is 38,” the study said. Milliman suggests that technological innovations such as algorithmic or robot-aided advice could greatly lower companies’ cost of delivering financial advice, making it more accessible to more people. Automated applications, for example, could collect responses to questionnaires, help construct individually tailored portfolios and improve performance reporting.

In addition to easier access to proper financial advice, the Asian market is ripe for innovative products and services that would allow elderly people to live better lives in their own homes instead of going to retirement centres. Australia is one country that is rethinking ageing, no longer viewing it as a “burden” but as a “most glorious opportunity”, according to Jane Mussared, chief executive of the Council on the Ageing South Australia.

“We are living longer because we are healthier than ever before but the problem is that we have yet to invent what we should be doing with these extra years of life. We haven’t adjusted the course of our lives, we haven’t adjusted the way we live, the way we work, the way we volunteer, the way we create art, and the way we play sports,” she told Asia Focus at the “Active Ageing” seminar, held by Resthaven and the Baan Sudthavas Foundation in Bangkok recently.

“Basically, we haven’t adjusted our vision of our lives to reflect longer lives, and my recommendation would be to throw the current rulebook in the air and start again.”

The new rulebook, she said, should emphasise different patterns of working and learning. Most societies put all their learning resources into children, teenagers and young adults, but there is little investment in learning in middle and later life, especially for people with limited resources.

“Poverty is compounded as we age … and we have to stop thinking that that the only time of life that is worth living is when you are young, and start thinking that life is worth living at any stage in your life, and you have to seize the opportunity,” said Ms Mussared.

Kelly Geister, senior manager of residential services at Resthaven Inc in South Australia, said that because Australian nursing homes are in danger of becoming overcrowded, the solution is to find ways for older people to remain in their own homes as long as possible.

“The government is putting funding into that avenue, including community care packages and the staffing that goes with that, to keep them at home as long as they possibly can. People are in their own environment with a proper support system until they are unable to cope any further and then they come to us (nursing homes),” she told Asia Focus.

Publicly provided elder care in Australia operates on four levels, she explained. For example, a person assessed at level one would be eligible for basic domestic assistance such as help with cleaning and gardening for one or two hours a week. Level-four assistance, meanwhile, involves high-care clients who require medication management and other assistance with daily living. The care packages also include certain sums of money over which pensioners have direct control based on what they feel they need most. For example, a person living at home might need someone to help with showering but would prefer to spend that money to pay an assistant to help with shopping, and this is allowed. That kind of flexibility is not always possible at a nursing home. Meanwhile, technological innovations such as sensors connected to monitors or mobile applications offer the promise of greater safety and faster responses in emergencies, whether one is in her own home or in a nursing home.

“The staff will know that for example, Mr Smith in room 12 has activated his sensor mat as he stood up, if he has been classified as having a risk of falling, which is why there is a sensor mat in place,” said Ms Geister. “Or a person with dementia might not remember to ring the call-bell for assistance.

“GPS tracking technology is also coming into the market in Australia for residents who perhaps have a risk of wandering in the community. They could get watches with trackers to monitor where the elderly with dementia are going, or we can simply accompany them when the tracker shows that the person is leaving the facility for a stroll in the garden in order to keep them safe.”

Renuka Visvanathan, director of aged and extended-care services with Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Adelaide, says “ageing is a privilege” because not everybody gets to age. In her view, the best way to meet the challenges of a greying society is through education.

“With knowledge, then everyone is prepared and this involves the education of health professionals and the education of consumers,” Prof Renuka told Asia Focus.

Consumers in this case are not only the elderly themselves but also their families, neighbours and community members, who all need to learn what older people need and how they should be treated. “Dementia is a classic example,” she said, adding that media such as YouTube could be valuable in disseminating videos that show how to be more considerate of older people who are struggling.

The next step is integrated care, which involves bringing together all the aspects of an older person’s care under one technology platform, as he or she is likely to have various specialists, medicine providers, and family members. A simple mobile application, for example, could make life much easier for older people who have trouble remembering when and what kind of medication they need at any given time. Examples include the Thailand-based startup PillPocket, and Singapore-based EyeDEA and GlycoLeap by Holmusk, which are now working with the pharmaceuticals division of Bayer Thai to develop integrated healthcare apps.

Source: https://www.bangkokpost.com/business/news/1426654/showing-our-age

English

English