Indonesia and Thailand charting clear maritime boundaries

Indonesia and Thailand are embarking on what could be a long and tedious negotiation process to determine the border of the exclusive economic zones (EEZ) between the two countries in the Andaman Sea.

But even before formal talks begin, both countries have to tune into the right mood for a friendly and fruitful negotiation in order to reach a satisfactory result.

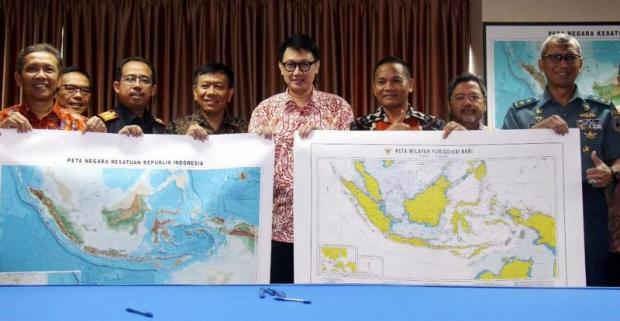

The contested EEZ located north of Indonesia’s westernmost province of Aceh is visibly delineated by purple dash lines that mark Indonesia’s claim, along a clear blue line of Indonesia’s continental shelf on the newly updated territorial map that the Jakarta government issued on July 14.

Both lines extend southwest in the Indian Ocean where Indonesia has a maritime border with India and southeast down along the Malacca Strait where it shares maritime boundaries with Malaysia and Singapore.

Negotiations with Thailand are still at a very preliminary stage, with informal exchanges of preliminary views following a meeting in late 2016, according to Bebeb Djunjunan, director for political, security and territorial treaties with the Foreign Ministry.

“We are still getting to know each other’s positions and trying to understand the principal guidelines for negotiations before we formally move on to the technical phase of negotiating the EEZ boundaries,” Mr Bebeb told Asia Focus.

A bilateral continental shelf bilateral agreement with Thailand and a trilateral agreement that also included Malaysia were settled in 1972. They were followed later in the 1970s by agreements on maritime boundaries on the seabed and maritime boundaries between Indonesia, Thailand and India in the Andaman Sea.

Mr Bebeb said there was no telling how long the new negotiations would take as they would not be purely technical, given that political and security considerations must also be taken into consideration.

It took Indonesia and Vietnam about 30 years to agree on the continental shelf boundaries, he added.

Indonesia has developed its position based on the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and all relevant international laws and practices. “UNCLOS rules are in our favour, but we will, however, find a win-win solution for both sides,” he said.

A prominent feature in the new map is the introduction of a new name — the North Natuna Sea — to mark the northern marine region of the Natuna Islands, which borders the southern tip of the South China Sea. Previously, the EEZ and the entire resource-rich maritime region around the Natuna Islands were referred to as the Natuna Sea.

Arif Havas Oegroseno, deputy for maritime sovereignty at the Coordinating Ministry of Maritime Affairs, said the change reflected the international tribunal ruling last year, which invalidated China’s claim to the entire South China Sea.

Indonesia is not a claimant to the South China Sea territorial dispute that involves four Asean countries including the Philippines. Manila took the case to international arbitration and received a favourable ruling, but Beijing rejected the findings. Since Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte took office, he has been downplaying the result and has been pursuing what he hopes will be a bilateral solution acceptable to both sides.

However, China’s claim, based on what Beijing refers to as a “nine-dash line” around the sea, overlaps in its southern end with Indonesia’s EEZ in the Natuna region.

Indonesia increased its occupation to reassert its sovereignty and strengthened its military presence in the far-flung maritime frontier after clashes last year with Chinese fishing vessels and Coast Guard ships in the waters around the Natuna Islands. China had argued then that its fishermen did not encroach and were only fishing in their “traditional fishing ground”.

The tribunal ruling favouring the Philippines was based on international jurisprudence that atolls or land formations in the sea that could not sustain human habitation could not be used as the basis to claim a 200-mile economic exclusion zone and continental shelf. Nevertheless, China is continuing an aggressive building programme, establishing military bases and other facilities and even promoting tourism to some of the islands it claims.

“We updated the sea column on the northern part of the Natuna Sea,” Mr Arif explained, adding that the new name was consistent with the nomenclature used for oil and gas blocks in the region, such as South Natuna, East Natuna and Southeast Natuna.

“The national team agreed to name it the North Natuna Sea,” he said, referring to a team comprising 12 government agencies that worked on updating the map.

China was quick to brand the renaming exercise “totally meaningless”, saying that the South China Sea name was already recognised globally with clear geographic boundaries, according to a Reuters report. Mr Bebeb said the new name was mainly for domestic purposes and the area was well within Indonesian maritime territory.

The new designation is a unilateral action and does not have any legal implications relative to the global consensus, said I Made Andi Arsana, a professor of geodetics at Universitas Gadjah Mada in Yogyakarta. “However, it is a political move to send a strong signal to the world, mainly China, that we assert our sovereignty to the sea region north of the Natuna Islands. That is why we call it the North Natuna Sea,” he told Asia Focus.

He likened the move to the decision by Manila to apply the name “West Philippine Sea” to the part of the South China Sea that it is contesting with China.

Mr Arsana said internationally recognised names and limits of maritime regions in the world, including the South China Sea, are listed in the International Hydrographic Office (IHO) 1953 document called S-23 on “Limits of Oceans and Seas”.

Indonesia could not participate in the determination of the names because it was not a member of the IHO at the time, having declared independence from Dutch colonisation only a few years earlier. The South China Sea name was used in the Indonesian territorial map that was drawn up based on old documents from the Dutch.

“The Natuna Sea name was used since 2002 in our map and now we have updated it with a new name,” Mr Arif said, adding that the updated map took into account a 2010 agreement with Singapore on maritime borders on the western and eastern parts of the Singapore Straits, and an EEZ agreement with the Philippines that Jakarta ratified this year.

Mr Arif said the long-term economic implication of the updated map was that Indonesia would have clear boundaries to govern natural resources exploitation in its maritime region, including fishing grounds. It will also provide clarity for the navy and other law enforcement agencies on where to conduct patrols.

Indonesia shares sea borders with India, Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore, Vietnam, the Philippines, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Australia and Timor Leste and land borders with Malaysia, Papua New Guinea and Timor Leste.

Source: http://www.bangkokpost.com/business/news/1297027/indonesia-and-thailand-charting-clear-maritime-boundaries

English

English