Cambodia: The riel throughout the years

In 1980, recreating a monetary and banking system from zero after the Khmer Rouge had abolished the use of money was a daunting task, particularly given the limited expertise at hand following the decimation of human resources in the country, according to the Sosoro Museum – Cambodia’s museum of money and economy.

The continuous efforts undertaken by the National Bank of Cambodia in the raising of awareness and the institution of policy tools, has gradually increased the overall use of the national currency, with a wider display of riel denoted prices in public and expansion in payments in riels (KHR). These efforts have even recorded an increase in the proportion of KHR designated loans (12.8 percent of total loans) and deposits (7.7 percent of total deposits) in the banking system.

According to Blaise Kilian, co-director of the Sosoro Museum, the riel has been relatively stable, specifically in 2020, considering that many regional currencies have faced pressure to depreciate and there is hope that this momentum of increased KHR usage will be maintained in 2021.

“Cambodia has been standing among the fastest growing economies in the world, whether we look at the last decade or at the last 20 years. While 2020 has been tough here, like everywhere else in the global context of the COVID-19 pandemic, the achievements of the past 20 years remain: GDP [gross domestic product] per capita has tripled, economic growth has averaged 7 percent per year and FDI [foreign direct investment] flows represent more than 10 percent of GDP,” he said.

Kilian added that this strong performance can also be measured against more qualitative indicators such as healthcare (infant mortality dropped from 106 per 1,000 live births to just 26), poverty eradication (population living under the poverty line) dropped from nearly 50 percent to 13 percent and education (lower secondary completion multiplied by nearly four times to 60 percent) among others.

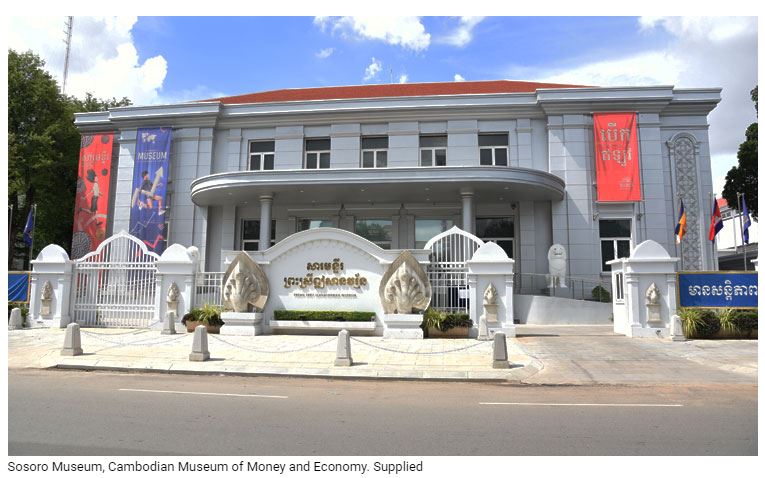

The Sosoro Museum plays a very important role in providing a unique perspective of Cambodia’s history and offers a sharper grasp of the constant interaction between money, the economy and politics.

It highlights fundamental facts and lessons learned from the country’s economic and monetary history as well as focuses on the money, credit, growth and inflation among others.

Because the museum is designed to be modern and interactive, it not only displays artifacts but also offers a narrative that contextualises the exhibition through historical records and audiovisual depictions of past and present Cambodia.

The museum displays 2,000 years of Cambodia’s history from economic and monetary perspectives. As such, a large part of the exhibition recounts the founding and subsequent management of the riel from its creation in 1955 to 1975 and then again from 1980 onwards.

The Sosoro Museum was the former town hall residence, in 1908, of the Phnom Penh municipality in 1920 and has been the museum of economy and money since 2012, displaying monetary collections and artifacts since the Funan era, a polity that encompassed the southernmost part of the Indochinese peninsula during the first to sixth centuries.

“As visitors dive into the exhibition, they learn how money, the economy, society and politics interact and therefore discover the relationship between sovereignty and the issuing of a national currency. All these elements create awareness about the national currency and therefore contribute to building a sense of ownership among visitors who get to learn more about the riel, its role in the economy and how monetary policy is managed,” said Kilian.

According to Kilian, the main highlight of the museum, in terms of monetary history, concerns the period of Angkor in which historians so far have not found any evidence of a monetary system in existence and where barter trade seemed to have prevailed.

“While Angkor was the greatest empire in the history of Cambodia, this lack of a monetary system may ultimately have proven to be a cause of weakness and decline, especially when faced with the growing competition of monetised neighbours. Research continues and findings may differ in the future but, so far, conclusions point in that direction,” Kilian added.

In rural areas, the riel is used for virtually all purchases, while in urban Cambodia and tourist areas, people mostly use the US dollar.

According to the National Bank of Cambodia (NBC), effective monetary policy is best conducted when the national currency is predominantly used. Because Cambodia is a highly dollarised economy, it is difficult for the central bank to successfully execute its mission given that the NBC is limited in the number of policy instruments it can use to promote sustainable economic development.

Kilian remembers during the transition of the early 1990s when confidence in the national currency was deeply shaken in the wake of sudden and massive inflows of US dollars during the United Nations intervention in Cambodia and it was also extremely challenging in terms of monetary policy.

Dollarisation started in the early ‘90s when the United Nations contributed humanitarian aid, refugees began sending remittances home and inflation, as high as 177 percent per year, further eroded confidence in the riel.

After the liberation from the Khmer Rouge in 1979, the riel was re-established as Cambodia’s national currency on March 20, 1980, initially at a value of 4 riels to $1.

The riel was subdivided into 10 kak or 100 sen. The central government gave away the new money to the populace in the form of civil salaries and government expenditures etc. to encourage its use.

Although the Khmer Rouge printed banknotes, these notes were not put in circulation because money was abolished after the Khmer Rouge took control of the country. The regime also printed a series of coloured banknotes in 1993 in territories controlled by them, but it was not used.

From 1991-1993, the United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia stationed 22,000 personnel in Cambodia, whose spending represented a large part of the Cambodian economy.

“The national currency massively depreciated from 800 riels per $1 in 1991 to 2,400 riels per $1 in 1993,” Kilian said.

He added that the crisis brought in by COVID-19 has proven to be a tough reality check for everyone.

“The consequences of the tourism industry’s collapse have highlighted the risks brought upon a narrow-based economy and therefore the need to tackle existing weaknesses: low industrial diversification, lack of high value-added production, low-quality education, weak standards and limited competitiveness including in the vast local SME [small and medium enterprise] landscape,” said Killian.

He stressed that these gaps need to be addressed in order to not only resume but also sustain growth beyond the crisis induced by the pandemic.

Source: https://www.khmertimeskh.com/50828868/the-riel-throughout-the-years-2/

English

English