Omicron Risk to Pin Rates in Indonesia, Malaysia: Decision Guide

(Bloomberg) — Central banks in Indonesia and Malaysia are expected to keep their benchmark interest rates at record lows Thursday in case a resurgence of Covid drive by the omicron variant sets back growth.

Bank Indonesia and Bank Negara Malaysia are likely to stay on hold at their first meetings of the year, reiterating their commitment to gradually unwind easy monetary policies once the economy shows sustained recovery. BI last adjusted its key rate in February 2021, while BNM has stood pat since July 2020.

Covid-19 cases have remained relatively low recently in the two Southeast Asian nations, but authorities fear the tally could shoot up quickly in coming weeks due to the pace of omicron’s spread and upcoming local holidays. Tough lockdowns to contain the delta strain sapped growth in both countries last year.

“I expect policy makers to highlight uncertainties related to omicron developments, particularly in terms of potential supply-chain issues and inflation implications, as well as in terms of the potential adverse impact on domestic demand,” said Tuuli McCully, head of Asia-Pacific economics at Scotiabank.

Investors will also be watching for clues to how BI and BNM will position themselves after the Federal Reserve’s latest signals that it could raise borrowing costs at least three times this year, possibly starting in March.

“U.S. monetary policy normalization will impact portfolio flows in and out of EM economies, and maintaining financial market stability will be particularly important for both BNM and BI, as foreign investor participation is relatively high in the Malaysian and Indonesian bond markets,” McCully said.

Here’s what to look out for in Thursday’s decisions:

Malaysia

BNM will keep the overnight policy rate at 1.75%, according to all 25 economists surveyed by Bloomberg. Analysts predict it will stay at that level for the first half of the year as Malaysia rides out a rocky start to 2022.

With Malaysia already grappling with community transmission of omicron, Health Minister Khairy Jamaluddin has cautioned that daily numbers could rise further as the multi-ethnic country celebrates Thaipusam this week and Lunar New Year in February.

Heavy rain that inundated parts of Malaysia — including a major port in its most industrialized state — have added to its woes. Flood damage is estimated at as much as 6.5 billion ringgit ($1.6 billion), with public assets and infrastructure accounting for one-third of the total.

“We expect BNM will focus more on ensuring economic recovery from the Covid-19 health crisis is sustainable this year before adjusting the overnight policy rate higher,” MIDF Research analysts Syed Kifni Kamaruddin and Abdul Mui’zz Morhalim said. They forecast a 25-basis point rate hike in the second half of the year.

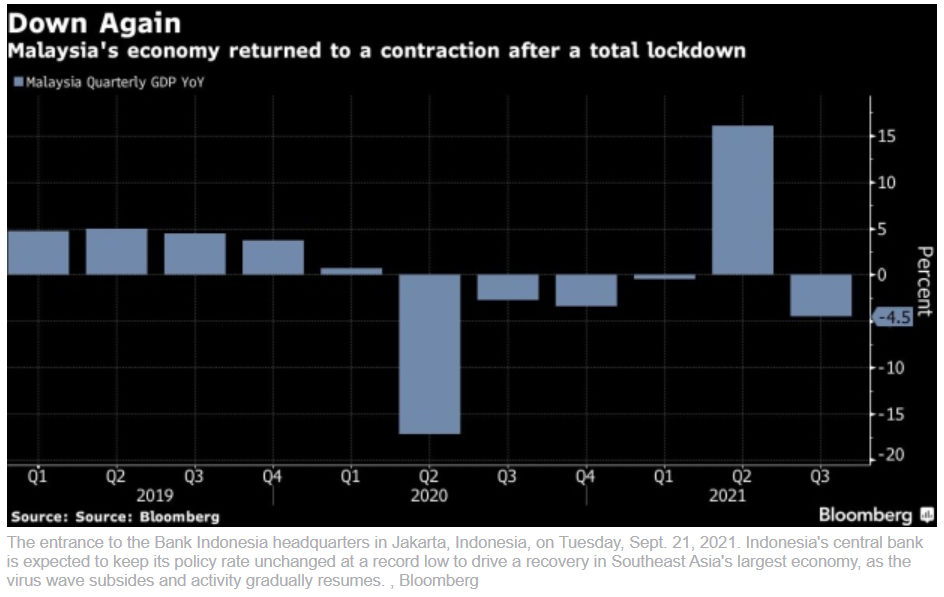

Malaysia’s recovery from the pandemic has been bumpy. The economy returned to contraction in the third quarter of 2021 on strict containment measures, the first major Southeast Asian country to report a renewed slump. The central bank estimates gross domestic product likely expanded 3%-4% in 2021 and should quicken to 5.5%-6.5% this year.

However, early signs have emerged that consumer spending is slowing, with the balance of risks skewed toward a moderate recovery path in the first quarter, according to RHB Bank chief economist Sailesh K. Jha. “It’s best to maintain a conservative stance on 2022 GDP growth,” he said, projecting it closer to 5.5%.

Indonesia

BI will maintain its seven-day reverse repurchase rate at 3.5% on Thursday, according to all 29 economists in a Bloomberg survey. The central bank has pledged to support growth for as long as inflation allows, though it may have to juggle that with the need to defend the currency.

Governor Perry Warjiyo said at the December meeting that Indonesia’s central bank does not have to move in step with the Fed, though at the time he expected the U.S. central bank to raise rates just once this year.

BI’s “pro-stability” stance could be put to the test if the Fed embarks on a more aggressive hiking cycle. Volatility has already hit Indonesian assets, with foreign funds selling off its bonds and the rupiah slumping 0.8% so far this year, the second-worst performer in the region.

While inflation in Southeast Asia’s biggest economy ended 2021 well below the central bank’s 2%-4% target, price pressures are expected to build this year as consumer activity returns to normal and with key commodities from coal to cooking oil in short supply.

That should prime BI to start raising rates from the third quarter, taking the benchmark to 4.25% by the end of 2022 and 5.00% by mid-2023, BofA Securities Asean economist Mohamed Faiz Nagutha said.

“However, if rupiah depreciation pressures rise significantly, risks of an earlier and faster rate hike cycle cannot be ruled out,” Nagutha said. “In this case, the terminal policy rate may also be higher than the pre-Covid 5%.”

English

English