Philippines: Lockdowns eased, poor go back to streets as housing fix stays on paper

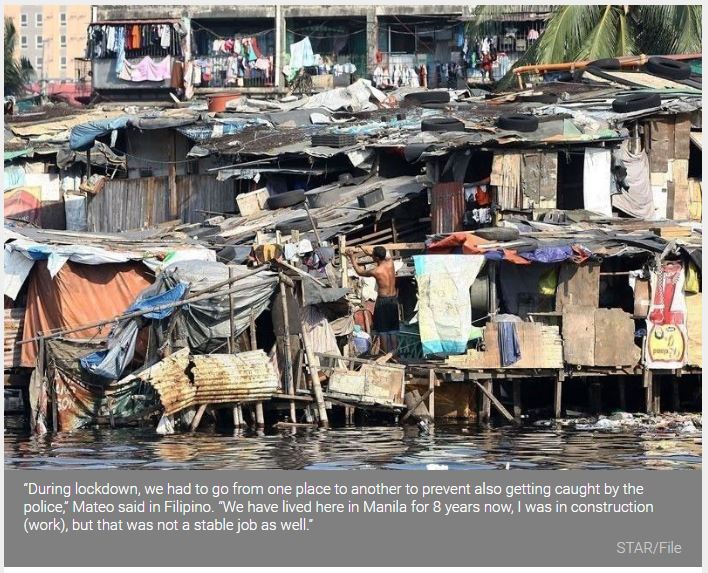

MANILA, Philippines — Lockdowns had been eased but while most Filipinos are still trying to stay home over fears of catching the deadly coronavirus, Rolando Mateo, 43, and his family of three do not even have a home to begin with.

We caught up with Mateo on Wednesday morning in a wet market in the poorer area of Makati City, kilometers away from the city’s towering offices. There, Mateo with mask on was begging for alms and when asked where his children were, he said they were doing the same. He was thankful though, going out no longer means possible jail time.

“During lockdown, we had to go from one place to another to prevent also getting caught by the police,” Mateo said in Filipino. “We have lived here in Manila for 8 years now, I was in construction (work), but that was not a stable job as well.”

Mateo’s predicament greatly reflects the disproportionate impact of the pandemic on the Filipino poor. While government flaunts statistics that showed poverty dropped to 16.5% in 2018, before the health crisis spread, the data masks a real class struggle getting left behind by the burgeoning middle class and the property sector that cash in on their purchasing power.

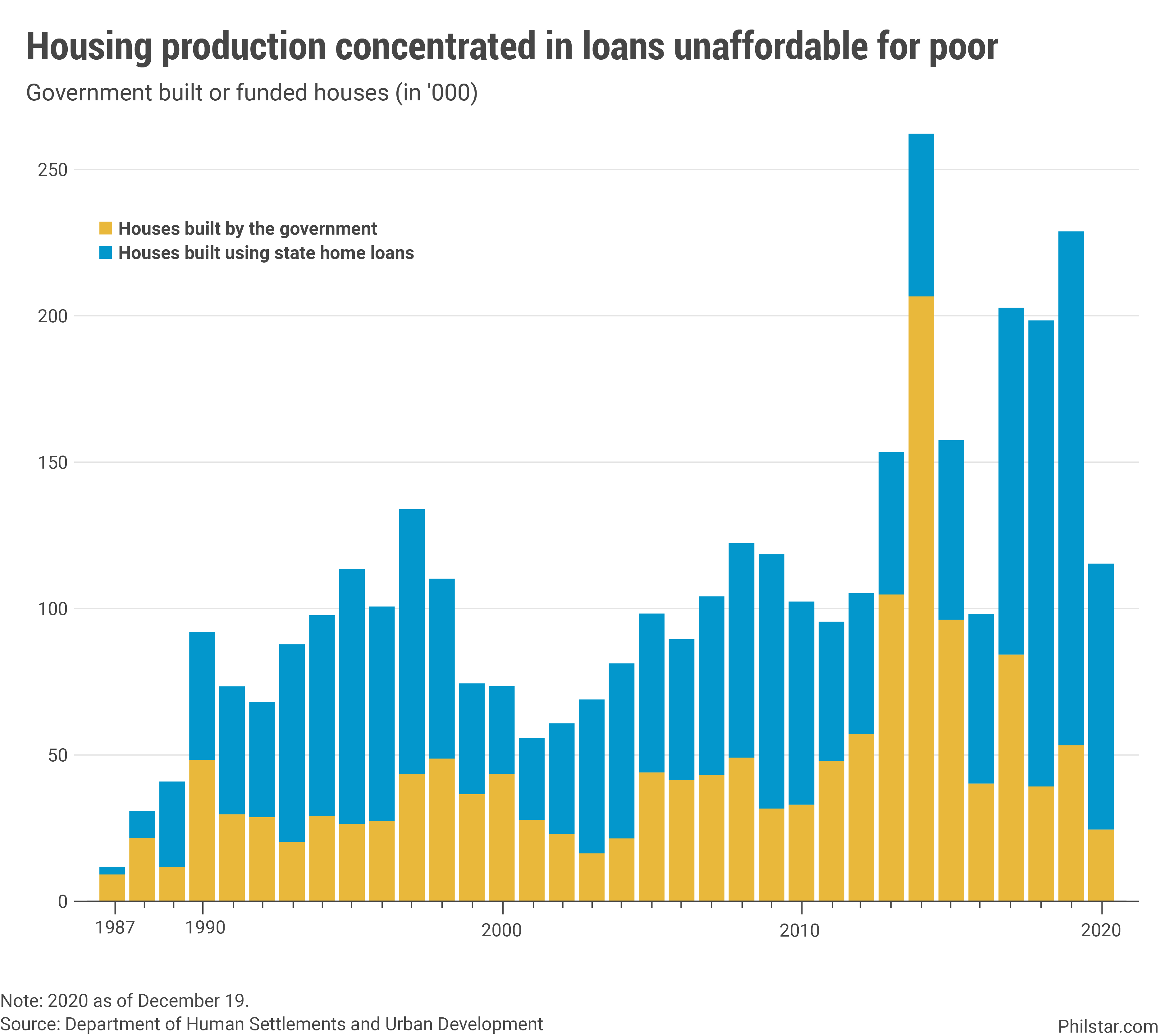

Housing regulators and firms said only around 30% of the Philippines’ 6.5 million housing backlog were meant for low-cost housing, or those catering for the likes of Mateo and family. The number seems small especially if you consider that the balance of 70% were shared by the middle and upper classes. Property prices had also started to go down because of oversupply, and many hope that can put owning homes within reach for the poor.

But the reality is, compounded by measly to no incomes, large families, and insufficient aid from public and private sectors, the housing gap is only bound to widen. On Wednesday afternoon, House legislators debated a resolution meant to declare a “housing crisis” in the Philippines. What that means and what will that do remain less clear, but the committee hearing did shed light on a housing gap now most likely to get handed over to the next administration to resolve.

“We are now moving towards our second year of the department this February 14. The first year was meant as transition period so we started a bit late,” Cristine Bello, a lawyer at the Department of Human Settlements and Urban Development (DHSUD), said.

“We also lack sufficient number of people to do that job, or the resources for that matter,” she said in Filipino. Last year, data showed the National Housing Authority only completed 46,605 units against a target of 68,095.

Indeed, birth pains re hitting the new department hard, making work more difficult and slower. Bello shared from a smaller office before with presence in only about half of the 13 regions, the bigger agency took time to establish more offices nationwide. Offices are of no use however without people, and Bello said currently those new branches are staffed with “three or a maximum of six people.”

It also does not help that the Duterte administration has not prioritized housing as much as other social projects like cash aid. For 2021, budget data showed the housing sector, which includes DHSUD and its attached agencies, got a measly P5 billion, down from last year’s P7.98 billion. In 2019, the allocation was only P3 billion. This year’s outlay specifically represents just 0.11% of the P4.5-trillion budget.

No idle lands in the Metro

The lack of funding greatly hampered work but currently, the department is doing its best to accelerate coming up with an inventory of government idle lands where housing programs may be established. So far, Bello said only 40% of local government units had been covered, and she is not sure when the entire project will be completed.

A clear sense of idle lands available for housing is critical to get the work done. The problem is national government does not hold most of the land, cities, municipalities and provinces do, and some of them are hesitant to share information.

To date, 14,605.07 hectares idle lands had been identified out of the 579,961.82 hectares covered area. The bad news is none of those lands are located in Metro Manila, one of the densest cities in the world where the poor typically go over belief of finding greener pastures. The capital region is estimated to have housing backlog of 666,202 as of 2017 which grows by nearly a million every year.

Tax breaks removed

Lawmakers themselves could not believe there is no space available for housing in NCR, a sprawling metropolitan area home to hundreds of malls. Meanwhile, the private sector, having fewer and fewer tax incentives to build low-cost houses, appealed for tax breaks to help bridge the gap.

The finance department succeeded in lowering the price threshold of homes exempted from value added tax to just P2 million from P3.2 million. The Corporate Recovery and Tax Incentives for Enterprises (CREATE) bill would try to lift that up to P2.5 million, but DOF is likely to recommend a veto to President Rodrigo Duterte, arguing that decades of tax incentives to the sector did not see developers catering to low-cost customers.

On top of that, Philippine Guarantee Corp. is likewise stopping providing guarantees to bank credit extended to housing “because they cannot compete with those offered by Pag-IBIG which is so cheap,” Alberto Pascual, president, said in the committee hearing. The problem is state housing loans typically cater to the working class, not the poor.

Currently, a 20-year housing plan is being drafted by the government to ensure continuity in project development. That could mean a longer wait for Mateo and his family practically living in the streets while a virus constantly threatens their lives. “People sometimes give us masks. I think that will do for now,” he said. — with Prinz Magtulis

Source: https://www.philstar.com/business/2021/02/11/2076989/lockdowns-eased-poor-go-back-streets-housing-fix-stays-paper

English

English