Malaysia: Insight – Taxing the digital economy

Tax authorities around the world believe that tax rules have not kept up with digitalisation, globalisation and new business models.

There is a concern that multinationals can make significant profits from countries where their customers are located, by using technology to deliver goods and services without an “onshore” physical presence and potentially without paying taxes in these countries.

The Covid-19 pandemic will increase the focus on taxing digitalised businesses for the following reasons.

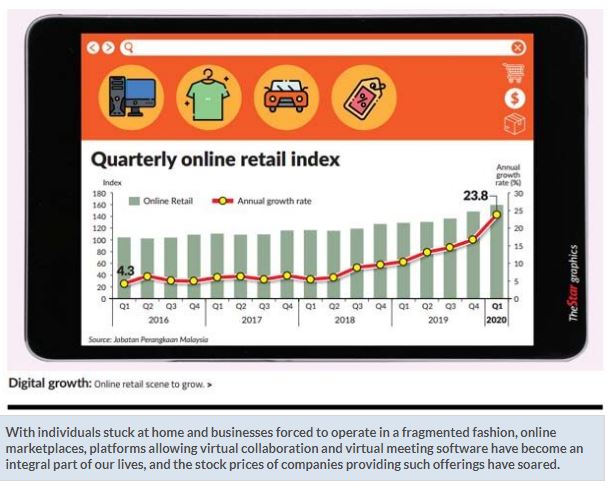

The digital economy has been the obvious beneficiary of lockdowns.

With individuals stuck at home and businesses forced to operate in a fragmented fashion, online marketplaces, platforms allowing virtual collaboration and virtual meeting software have become an integral part of our lives, and the stock prices of companies providing such offerings have soared.

Many other sectors of the economy are suffering. As tax authorities come under increasing pressure to fill the tax void caused by the pandemic, large digitalised businesses, which are perceived to be under-taxed and to have deep pockets, are obvious targets.

From an indirect tax standpoint, Malaysia introduced a service tax on imported digital services (STODS) from Jan 1 2020.

STODS is levied at 6% and foreign digital service providers must register in Malaysia, charge service tax and file service tax returns where certain thresholds are met. Digital services subject to STODS include online advertising, provision of online platforms, cloud storage and hosting services and digital content such as music, videos, software and apps. Malaysia does not have specific direct tax rules to tax digital transactions, relying instead on conventional tax rules.

Internationally, unilateral digital taxes have caused technical and political issues.

For example, the introduction of a Digital Services Tax (DST, which is being implemented by many countries) by France was viewed by the US to be “unreasonable and discriminatory” and unfairly targeting Silicon Valley, resulting in the US announcing retaliatory tariffs on various French products. There are also concerns that DST and similar taxes may result in double taxation, as countries may not allow tax credits or deductions for DST suffered elsewhere.

In view of such issues, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and the United Nations (UN) are working on multilateral solutions.

The OECD’s two-pillar project, referred to as BEPS 2.0, began in earnest in early 2019. “BEPS” here refers to the OECD’s 2015 “Base Erosion and Profit Shifting” project, where 15 Action Plans were released to address perceived profit-shifting by multinationals.

The OECD had initially targeted to reach a consensus on BEPS 2.0 by the end of 2020, but recently announced that this timeline will be pushed back to mid-2021.

The BEPS 2.0 project will result in widespread changes to the global tax landscape and will also impact cross-border businesses which are not necessarily “digital” in nature.

The “Pillar One” proposals will impact the locations in which taxable profits are recognised, with “market jurisdictions” where users or customers are based, being allowed to tax certain profits despite the supplier having no physical presence there. These proposals will require a significant revamp to transfer pricing rules and documentation currently in place in relation to related party transactions.

The “Pillar Two” proposal intends to ensure that a yet-to-be-determined minimum level of taxation is imposed on all business profits. This could significantly impact tax policy, including decisions by countries on setting corporate tax rates, balancing corporate tax and indirect tax revenue, and structuring incentive regimes.

The UN in the meantime proposed recently to add a new Article 12B into tax treaties to be negotiated between countries.

This proposed Article, together with corresponding updates to domestic tax laws, would allow countries where users are located to tax income from “automated digital services” rendered by non-residents, possibly by way of a withholding tax. Interestingly, many of the automated digital services covered by the proposed Article 12B are similar to those covered by the Malaysian STODS regime.

It is hoped that international consensus is reached soon and that the separate workstreams being run by the OECD and the UN do not lead to uncertainty and delays.

Given the need to raise tax revenues, any delays in reaching a multilateral solution will likely result in a proliferation and reinforcement of unilateral actions across the globe.

Whilst the OECD, the UN and tax authorities grapple with digital tax rules, the tax treatment of cryptocurrency as a medium of exchange or as an investment class also needs to be addressed.

Some countries started issuing cryptocurrency tax guidance as early as 2014, but authorities may struggle to keep up with new cryptocurrency transactions and products, such as crypto borrowing, lending and De-Fi and crypto forging or staking.

It will be interesting to see if digital tax proposals will feature in Budget 2021. The government and Malaysian multinationals will need to closely monitor the BEPS 2.0 developments as these will undoubtedly impact tax policy around the world, including Malaysia.

Anil Kumar Puri is a partner in Ernst & Young Tax Consultants Sdn Bhd. The views reflected above are the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the global EY organisation or its member firms.

Source: https://www.thestar.com.my/business/business-news/2020/11/03/taxing-the-digital-economy

English

English