Western thoughts on benefits of Cambodian BRI initiatives evolving

The success of China’s Belt and Road Initiatives (BRIs) in Cambodia will depend on what the project is and how productive it will be, according to experts who have analysed China’s white paper on foreign aid and development.

That document, released last month, was light on fundamental details for many projects, including the source of funding and how much they would cost.

BRI projects have been criticised for their lack of transparency, with detractors arguing that the projects are indicative of Beijing exercising its soft power to pursue global dominance on the backs of developing nations, sometimes burdening them with debt for “white elephant” projects.

David Dollar, a former economic and financial emissary to China for the US Treasury, takes issue with this kind of one-size-fits-all assertion.

“If Cambodia borrows from China and builds needed power stations, roads and rail, then it’s win-win because the economy will grow faster and nations can repay China through some of the additional GDP [the projects generate],” Dollar said.

US-based transparency lab AidData executive director Bradley Parks elaborates, saying his organisation has noted a “sharp spike” in special purpose vehicles (SPVs) to fund BRIs in Cambodia over traditional concessionary loans since 2014.

SPVs are independent entities created to design, finance and execute specific projects that will eventually generate revenue.

The China Development Bank (CDB), the Export-Import Bank of China (Exim Bank), the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC), the Bank of China and the China Construction Bank (CCB) have all spun off entities for BRIs in Cambodia.

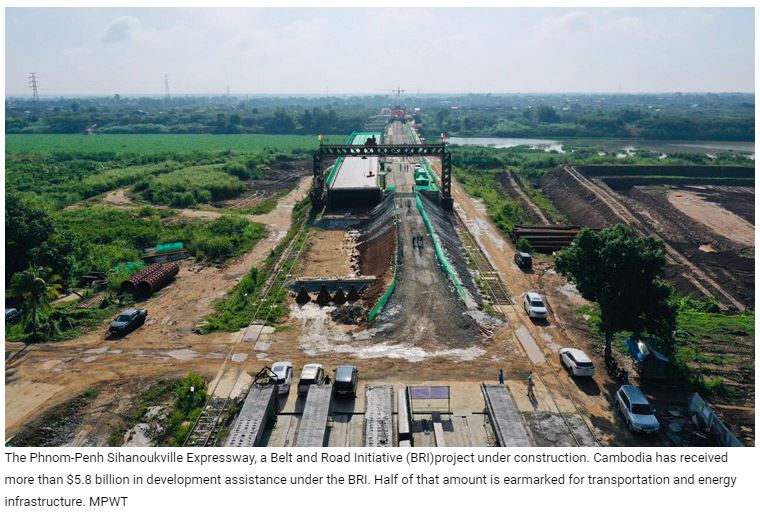

This includes the $660 million SPV formed for the construction of the Siem Reap Angkor International Airport. Similarly, the China Road and Bridge Corp SPV was funded by a $1.56 billion syndicated loan to build the Phnom Penh-Sihanoukville Expressway. That syndicate included the CDB among its participants

The shift to SPVs from concessionary loans means that debt is issued commercially. As a result, the Kingdom will have to ensure that the projects are viable, well-managed and generate enough revenue to pay off the loans.

Dollar pointed out that if the projects proved to be white elephants that did not make the economy grow faster, then Cambodia would be left with debt but not enhanced productive capacity. He added, however, that Cambodia has a lot of development partners, so it makes sense to draw on them for analysis of the infrastructure projects.

“I also think it is important to consult with communities because they have to accept the new infrastructure for it to be productive,” added Dollar, who now hosts the popular “Dollars and Sense” podcast. His podcast covers international trade and diplomacy.

Bradley Parks noted, “[SPVs] are especially attractive to banks that are guided by the pursuit of profit [and as such] the project in question is expected to generate enough revenue to fully repay the loan principal and interest.”

Chinese concessionary loans, believed to be the primary source of funding for BRI projects, offer Cambodia debt at 0-2 percent interest to be paid over 15 to 20 years. China is the Kingdom’s primary lender. Cambodia’s 2021 debt-servicing obligations to China currently amount to $225 million, according to the World Bank.

Parks and his colleagues from The College of William & Mary, a public research university in Williamsburg, Virginia, in the US, Development Gateway Inc, an international nonprofit organisation that provides technical tools and advisory services to country governments and development groups, and Brigham Young University, a private research university owned by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and located in Provo, Utah, USA, published a study that put the white elephant hypothesis to the test.

They found that Chinese government-financed development projects yield similar economic growth dividends as western development projects do.

“For the average recipient country, a doubling of Chinese government financing leads to a 0.41 percent increase in economic growth,” noted Parks.

“These are not charitable projects. They require the host country to undertake commitments on reform and financial risk that are considerable. As a result, [countries] tend to downplay these projects until they are completed and the results are visible,” said Rafiq Dossani, RAND Corp’s director at its Centre for Asia Pacific Policy. RAND Corp is a US nonprofit global policy think tank that offers research and analysis to the US armed forces. It is financed by the US government and private endowments, corporations, universities and private individuals.

“In the intermediate stage, it could be important to develop good governance structures for trade and financial integration. If Cambodia can work on this, it will substantially improve the benefits of BRI projects in transportation and energy infrastructure.”

Source: https://www.khmertimeskh.com/50810941/western-thoughts-on-benefits-of-cambodian-bri-initiatives-evolving/

English

English