Thailand: A powerful statement

For industrial operators, a loss in power supply for even a split second could lead to catastrophic damage to their business. But an even greater fear for some operators would be if their power supply contracts were controlled by a monopoly, extracting high prices without competition.

Electricity is deemed both a necessity and a public utility in Thailand. The state plays an important role both in generation and distribution of power, and acts as a regulator supervising pricing and business investment plans.

A dispute broke out over SET-listed Global Power Synergy Plc’s (GPSC’s) full takeover of SET-listed Glow Energy Plc after former Finance Minister Korn Chatikavanij publicised his concerns about the deal, stating it would give GPSC a monopoly on all power purchase agreements (PPAs) in the Map Ta Phut industrial estate.

GPSC is a subsidiary of PTT Plc, the national oil and gas conglomerate, and PTT is a large state-owned enterprise.

Mr Korn said the acquisition might violate the constitution’s Section 75, which prohibits the government from running a business competing with the private sector, except for necessary cases.

Both SET-listed firms are ranked among Thailand’s top 10 largest power operators.

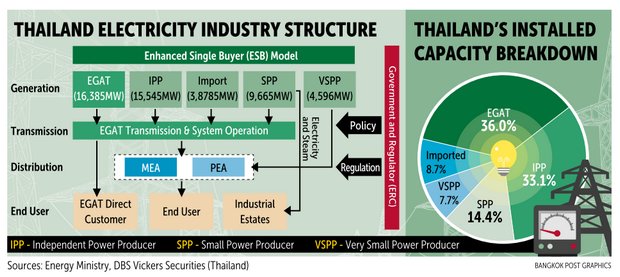

Energy policymakers are planning to move away from an enhanced single buyer (ESB) system for the country’s power business after the model was implemented for the last three decades. Under ESB, the Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand (Egat) solely owns the transmission system, while the Metropolitan Electricity Authority (MEA) and the Provincial Electricity Authority (PEA) purchase some portion of electricity generated and distribute it to users.

When Thailand’s economic growth expanded rapidly during the 1980s and 1990s, power demand in the industrial sector also increased. Ultimately, power supply became a critical issue because Egat was the sole controller and PEA and MEA, both state-owned, were the sole distributors.

GENERATING CAPACITY

State-owned enterprises have financial limitations preventing them from expanding power-producing capacity. They have to seek massive capital expenditure to meet their huge production targets.

This explains why energy policymakers have decided to partially deregulate the system by opening power trading to private investors.

Private investors can bid for licences for power plant development and operation, for both large and small plants. But some capacity must be sold to users via state organisations through PPAs, while the remaining capacity can be sold directly to users in terms of private PPAs (PPPAs).

This model is a trade-off between private investors and state entities to mitigate capital expenditure under the ESB model.

As a result, a stable power grid is the most crucial factor because oil refineries and petrochemical crackers can be damaged if the power supply is interrupted. Such interruptions happened frequently in the past before the ESB model was implemented.

Since then, the power plants, which are run by private operators, have congregated in the Eastern Seaboard area, while oil and gas operators have established their business presence in this precinct for over three decades. For instance, both GPSC and Glow are among energy companies operating in the Map Ta Phut industrial estate

Before the takeover in June, Glow controlled 60% of the PPPAs in Map Ta Phut, while GPSC and PEA each had 20% of the agreements.

Policymakers are considering a shift from the ESB model, deregulating the market as renewable energy becomes more cost-competitive under the newly revised National Power Development Plan (PDP) for 2015-36.

Officials will set up a time frame for an implementation plan and establish a business model for district power generation and supply in local communities via solar rooftop panels.

This power trading method, also known as peer-to-peer power trading, can use blockchain technology.

More than two decades ago, energy policymakers initiated free-market competition under a power-pool system, but it was ultimately scrapped because the 1997 Asian financial crisis shuffled priorities.

ARM’S-LENGTH PRINCIPLE

GPSC purchased 69.11% of shares from French-based Engie Group, the majority shareholder of Glow. The remaining 30.89% of shares are expected to be bought through a tender offer. The deal is expected to be worth 139 billion baht and completed by November.

In addition to Mr Korn’s publicised concern, some customers with PPPAs under Glow nearly ended their purchase contracts upon learning that the company would be acquired by PTT. These customers are subsidiaries of SCG Chemical Co, a petrochemical arm of Siam Cement Group.

In addition to Mr Korn’s publicised concern, some customers with PPPAs under Glow nearly ended their purchase contracts upon learning that the company would be acquired by PTT. These customers are subsidiaries of SCG Chemical Co, a petrochemical arm of Siam Cement Group.

Details of the PPPAs have not been revealed, but SCG signalled to the public that GPSC is likely to prioritise renewal of PPPAs to favour its sister firm, PTT Global Chemical Plc (PTTGC).

PTTGC and SCG Chemical are major competitors in the Map Ta Phut industrial estate.

Mr Korn also sent his petition letters to the Energy Regulatory Commission (ERC) and the Office of the Ombudsman to register his objection to the acquisition.

The ERC, as the country’s power business regulator, will conclude its consideration of the deal by October. The agency has a 90-day time frame to decide on the acquisition, said former ERC commissioner Viraphol Jirapraditkul.

GPSC submitted an inquiry letter to the ERC because the company was concerned about its acquisition, he said.

Mr Viraphol said the ERC will invite all related stakeholders in the matter to clarify the facts before it renders judgement within its legal authority.

Power tariffs for renewed PPPAs have to be agreed upon by both power buyers and sellers. The ERC only monitors to ensure fairness in the business sector, Mr Viraphol said.

Toemchai Bunnag, GPSC president and chief executive, said the company hopes to ease the anxiety among Glow’s customers, ensuring them that none will be affected by the acquisition.

All conditions, such as electricity fees and services under their original agreements, will be honoured because the power business naturally involves long-term contracts, which clearly specify fees and production volume.

All conditions, such as electricity fees and services under their original agreements, will be honoured because the power business naturally involves long-term contracts, which clearly specify fees and production volume.

Sale prices will depend on market rates under the arm’s-length principle, a condition that means the parties involved in a transaction are independent and on an equal footing. The duration of Glow’s existing contracts is more than 10 years on average.

The main objective of the transaction is to synergise both companies’ strengths to boost efficiency and power security for local and foreign companies operating in Map Ta Phut, Mr Toemchai said.

The acquisition will reduce operating expenses, benefiting both GPSC and its customers, he said.

NO MONOPOLY

Praipol Koomsup, a former economist at Thammasat University, said it seems GPSC will have plenty of power capacity after acquiring Glow’s assets, but this will not constitute monopoly power in the country or in Map Ta Phut.

In particular for Map Ta Phut, GPSC will control 80% of PPPAs after completing the transaction.

Mr Praipol said the country’s power market has semi-free competition, but all power business movements have to be approved by the ERC.

Mr Praipol said the country’s power market has semi-free competition, but all power business movements have to be approved by the ERC.

Every size of private power producer sells the majority of its electricity to Egat, which controls the national grid, he said.

“The ERC determines monthly electric rates every four months, deciding on the fuel tariff rate,” said Mr Praipol, a former vice-minister of energy. “The ERC also regulates all aspects of Thailand’s power market, so private power producers barely have free competition and are unlikely to gain too much power.”

Though factories in industrial estates are free to choose their power distributors, the purchase agreements must have certain power prices over the long term, he said.

“The deal between GPSC and Glow cannot constitute a monopoly, and GPSC cannot take advantage of Glow’s customers,” Mr Praipol said.

Wisate Chungwatana, chief executive of SET-listed WHA Utilities and Power Plc (WHAUP), said the takeover helps both companies because Engie plans to quit its fossil-fuel-based power generation and transform into a clean energy company, while GPSC is targeting future business operations for electricity rather than fossil-based oil.

“Our parent WHA Corporation Plc believes this complaint coming on the eve of the general election countdown means it could be politically motivated,” Mr Wisate said. “This will be a win-win case rather than a monopoly.”

SPECIFIC LAWS

Boonyarit Kalayanamit, director-general of the Internal Trade Department and acting secretary-general of the Office of Trade Competition Commission (OTCC), said the acquisition does not come under the purview of the Trade Competition Act of 2017, as energy businesses are regulated by the ERC.

“There is already a specific law in place that governs energy business competition,” Mr Boonyarit said. “It also contains a section that supervises [prevention of] an energy monopoly.”

The Trade Competition Act states that any disputes of any businesses that already have a specific law regulating them will be decided based on such law, he said.

In Thailand, six sectors have specific laws regulating their business: telecommunications, finance, energy, insurance, aviation and the stock exchange.

The act is aimed at promoting fair trade under international standards and preventing formation of cartels or monopolistic trade practices.

The Trade Competition Act was published in the Royal Gazette on July 7, 2017 and went into force on Oct 5.

The law includes expanded powers for the OTCC, making it independent from the government.

The seven-member OTCC was approved by the cabinet on Sept 4 this year. Commission members have been assigned by the cabinet to hold a joint meeting later to choose the chairman and one vice-chairman before submitting nominations to the prime minister for approval.

Other important provisions of the new law include a more detailed definition of a business operator with market dominance, plus changes on merger control, anti- competitive agreements, unfair trade practices and penalties and sanctions.

Penalties and sanctions are calculated as a percentage of the turnover of a business in the year the offence was committed, or if a merger violates the law, a percentage of the value of the merger. This may cause penalties to be higher than the fixed maximum fine under certain circumstances.

The act clarifies the scope of unfair trade practices as intervening in the business operations of other operators without reasonable grounds.

Other characteristics classified as unfair trade practices include unfairly fixing the price levels of goods or services; unfairly setting conditions that limit the ability or opportunity of other operators to conduct manufacturing, trade in goods or services, or procure credit; and suspending, reducing, or limiting the provision of goods or services, or causing damage to goods, with the intention of reducing market supply to below demand.

Source: https://www.bangkokpost.com/business/news/1541314/a-powerful-statement

Source: https://www.bangkokpost.com/business/news/1541314/a-powerful-statement

Thailand

Thailand