COVID-19 risks inflicting long-term economic pain on Myanmar

Even before COVID-19 hit Myanmar, businesses in the commercial capital were struggling.

Ko Thaw Zin, who runs his own restaurant in Yankin township, struggled with a shortfall in revenue due to dwindling tourist arrivals as well as rising costs brought about by a government move to raise electricity tariffs – a move it said would end debilitating power cuts in the country.

“But there are still power cuts here. Power cuts are very bad and always bad for us [restaurants and shops],” Ko Thaw Zin said.

“The amount of electricity we have to use is enormous and we need a reliable supply to operate [smoothly]. The government still doesn’t get it.”

Then the pandemic struck.

“Many restaurants in Yangon are now forced to close. We have lost around 80pc of our revenue. Even if there is a good amount of food delivery sales, it’s barely sufficient to cover our operating costs,” he said.

Cutting employees or putting staff on furlough is already the “best case scenario”, he said. “The worst is to pack up and leave.”

The economic shock from the pandemic deals a heavy blow to an already difficult situation for the majority of tourism, food and beverage and retail businesses, which had been struggling from lower tourist arrivals caused by the northern Rakhine crisis as well as rising costs.

Other important industries like manufacturing and agriculture have also taken a hit, while stalled investments in banking and oil and gas could impact future growth.

But the government still has some headroom to take on more financing and could use the current crisis as an opportunity to improve things for the longer haul.

Manufacturing and poverty

Manufacturing and tourism, two sectors hardest hit by the crisis so far, account for 7 percent and 5pc of Myanmar’s total employment in the formal economy, according to the 2014 census data. Since then, manufacturing has expanded to represent a larger part of the economy, driven by growth in the garment sector.

But things are now taking an unfortunate turn. Garment workers in Yangon went on strike last month in a bid to halt imminent layoffs amid a slowdown in production brought about by the pandemic.

So far, over 60,000 workers across the country have lost their jobs after 175 factories were forced to shut down as a result of cancelled orders and disruption of raw material supplies, according to labour ministry permanent secretary U Myo Aung.

Peter Yates, governance specialist with the Asia Foundation, added that “necessary social distancing and increased restrictions on movement will have a dramatic impact on the economy and on peoples’ livelihoods, and governments must keep both imperatives in mind when crafting their policy response to ensure social cohesion is maintained.”

The disruptions to retail and manufacturing may not be as temporary as initially expected. Demand from the EU, by far the biggest market for Myanmar garment exports, has already fallen. Quarantine measures, illness and negative market sentiment will suppress demand and recovery will only be gradual, according to Agathe Demarais of the Economist Intelligence Unit.

Unemployment in urban manufacturing has also hit families in rural areas.

“Remittances sent home by workers have gone down or disappeared altogether. More than half of the garment workers are internal migrants and they often remit around half or slightly less than half of their wages back home. This already has a pretty significant impact on the villages, particularly those who live near the poverty line,” said Jacob Clere of Smart Textile & Garments, an EU-funded programme which supports reforming the industry.

While a €5 million (US$5.43 million) emergency fund from Brussels is being used to give monthly payments of K75,000 to tens of thousands of unemployed workers, “at this stage, we aren’t sure how many factories can hold themselves together, and how many will fail,” Mr Clere said.

Finance ministry data suggests that 40pc of households in Myanmar now live below or close to the poverty line. Many households cannot afford for all working members to forego work for much more than a week. This means that Myanmar needs to find a way to support local workers to stave off widespread poverty.

It is also before factoring in the thousands of migrant workers returning jobless from the border. Data shows close to 46,000 migrant workers have returned from the Thai and Chinese borders up to mid-April. Thousands more are believed to have crossed by unofficial border crossings.

Stalled investments

Another area of concern is slower inward investments into the country as the virus continues to play out. Private sector decisions to put major investments on hold would have a much longer-term impact on the economy.

Energy stands out among the industries affected.

Australia’s Woodside Energy this month announced significant cuts to its global operating and investment budgets for 2020. In Myanmar it is a partner in an exploration agreement inked last December on Block A6 in offshore Ayeyarwady Region. A6 will be Myanmar’s first ultra-deepwater natural gas field project, with a projected daily output of 400 million cubic feet, more than a fifth of Myanmar’s existing daily output.

Speaking in a teleconference with investors, Woodside Energy managing director Peter Coleman categorised Myanmar as discretionary capital expenditure which the firm will “dial back even more… if things get worse.”

Although A-6 and exploration projects remain in its revised investment plans, Woodside said in March that it would reduce investments this year by about 60pc to around $1.7-1.9 billion. Over the longer term, Chief Financial Officer Sherry Duhe said projects in Myanmar have been “scaled back”.

When responding to questions from The Myanmar Times though, a Woodside spokesperson said the company will continue work at A-6 with the intentions of moving forward.

The government has also promised to launch a bidding round involving 33 blocks for foreign operators this year but it is unclear how the plunge in global energy prices will affect investor appetites.

Such delays would affect Myanmar’s ability to produce gas domestically, develop energy security and draw investment capital. Offshore gas sales constitutes the most important source of government revenues through exports to China and Thailand.

The pandemic could also deter foreign banks planning to expand in Myanmar. Seven Asian banks were recently granted operating licences in the country but three South Korean banks have already temporarily suspended their investment plans.

Managing bad debt

In the local banking sector, the concern is rising bad debt.

Research from previous economic crises suggest that non-performing loans (NPLs) spike during the acute phase of the crisis before returning to the normal baseline within eight months of the peak, said Andrew Bauer, a consultant with Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI).

During the 1997 Asian financial crisis, Indonesia and Thailand’s non-performing loan rates rose to 40-50pc at their peak.

“Until we know more about the effect COVID-19 containment measures are having on the Myanmar economy and have more details on bank balance sheets, we won’t know the extent of the damage on Myanmar’s financial sector,” Mr Bauer told this newspaper.

Among the distressed are borrowers who rely on brick and mortar consumer spending, notably shopping malls, airports and hotels.

Office providers are suffering too. In Yangon, developers of Grade A offices are experiencing delays in construction, which could worsen if work has to be suspended in the future.

Meanwhile, warnings of potential bank runs have surfaced. According to a coronavirus policy report by London-based International Growth Centre, Myanmar’s experience with two major banking collapses in the last 30 years makes a run on the banks likely despite better institutional provisions now being in place.

“The central bank now acts as the lender of last resort to retail banks, which was not the case in the 1990s-2000s, but the widespread absence of trust in public institutions remains and has made a panic spiral more likely,” the report noted.

Officials are aware of the risks. In mid-March, the central bank instructed local banks to stock up sufficient cash at their branches and ATMS across the country.

Food security at risk

Agriculture, Myanmar’s most important sector which accounts for about 30pc of GDP and over 50pc of total employment, is also at risk from the pandemic and that is raising concerns on longer-term food security.

The industry is dominated by smallholder farmers, who have been affected by border trade disruption and restrictions on the movement of produce, labour and consumers.

“What we have seen in other parts of the world, including in the region, is changing consumer behaviours driven by income pressures and movement restrictions,” said Elliot Brennan, a researcher at the Institute for Security and Development Policy.

Regionally, this has led to falling prices of vegetables, which hurts smallholder farmers and could affect future planting. “Smallholder farmers are a crucial link in the health of the economy and society. They must not be forgotten by policymakers during the COVID-19 pandemic. To do so could have a dreadful ripple effect,” Mr Brennan said.

Opportunity for change

The economic fallout from COVID-19 will stretch public finances and could even see the country seek financing from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and other financial institutions. During a teleconference with the IMF and other ASEAN countries on April 24, central bank governor U Kyaw Kyaw Maung said serious considerations will need to be taken in the event that the outbreak drags on and economic growth continues to slow.

To mitigate against a slowdown, U Kyaw Kyaw Maung said the central bank is preparing applications for the IMF’s Rapid Credit Facility and Rapid Financing Instrument.

“Given the financial and economic impact that is already taking place, I think the math will come down in favour of taking on some of these grants and loans,” Ko Nyantha Maw Lin, owner of the agribusiness Burgundy Hills Co, told The Myanmar Times.

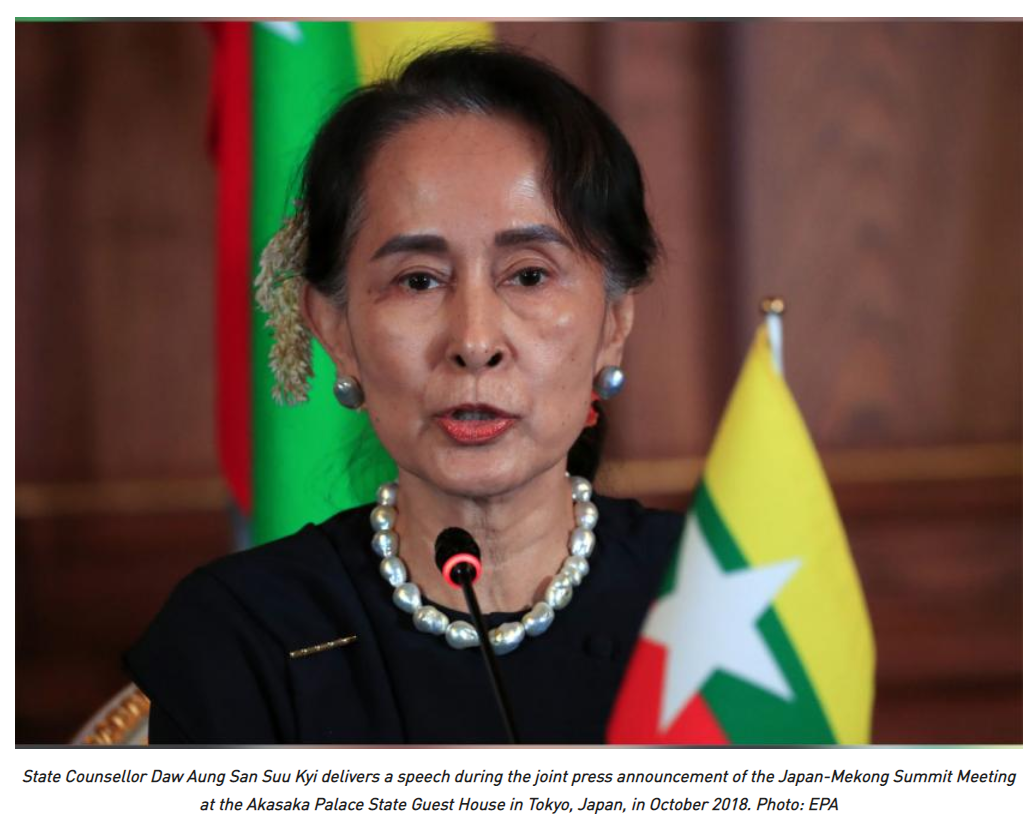

“The significance of COVID-19 induced tax revenue shortfalls cannot be downplayed, with anticipated revenue underperformance requiring reallocations of government spending to create space for COVID-19-related outlays, and policies,” Daw Aung San Suu Kyi wrote in the report’s foreword.

The stimulus package covers a range of monetary policy responses, including a 3pc cut in interest rates, and fiscal measures like tax credits and soft loans to local enterprises guaranteed by the government.

To do this, the government will face growing pressure to borrow or print money and spend a lot more than what it has budgeted to keep the economy afloat.

Prior to COVID-19, the IMF estimated that the tax revenue this year ending September 30 would be 6.9pc of GDP, little changed from the past two years, with total revenues of 18.1pc of GDP. Net borrowing was anticipated to be 4.1pc of GDP.

No new estimates are yet available but, with the economy crashing and the stimulus plan in place, tax revenue is expected to experience a sharp fall and the fiscal deficit will widen.

Nevertheless, Myanmar’s debt-to-GDP ratio is still much lower than other emerging countries, giving it some headroom for more borrowing.

“The good news is that the Union government has a lot of fiscal space. Public debt levels are low by regional standards and debt servicing represents a modest 7pc of government revenue. This means that there is significant room to temporarily borrow to pay for an economic stimulus and cover the shortfall in revenues caused by the global crisis,” said Mr Bauer of NRGI.

More importantly, the government should not neglect efforts to reform the economy that were underway before the pandemic struck.

Mr Bauer urged Nay Pyi Taw to continue reforming state firms running the oil and gas, timber, mining, telecoms, ports and electricity supply in order to improve public finances for the future. These state firms regularly generate approximately 50pc of the Union’s fiscal revenues, but they also spend about as much.

“What’s more, state enterprises regulate much of Myanmar’s economy and, through their contracting and licensing roles, these firms help determine who in Myanmar has access to resources and who does not. Reforming state economic enterprises is the key to unleashing Myanmar’s economic potential,” Mr Bauer said.

Vicky Bowman, head of the Myanmar Centre for Responsible Business, says the government has taken some rapid and concrete measures to cut red tape and improve efficiency for businesses amid this crisis.

For example, applications to extend trade registration certificates will now be carried out online until the end of July to help traders bypass the need to physically go to the trade department offices in view of COVID-19.

Export and import permits have been issued online since April 1 and HS code lines for 73 export items and 742 import items. Starting April 20, the customs department also reduced customs duties for businesses operating with the Myanmar Automated Cargo Clearance System.

Paperwork has also been streamlined, with an electronic version of Form D for preferential tariff treatment in ASEAN to be issued to simplify procedures between all the ASEAN countries.

“Let’s hope it also accelerates the introduction of digital government, which is an important step to reducing petty corruption,” Ms Bowman commented.

Source: https://www.mmtimes.com/news/covid-19-risks-inflicting-long-term-economic-pain-myanmar.html

English

English